2️⃣ Looking for modular circuits

Learning Objectives

- Learn how to use our linear probe across multiple layers

- Apply activation patching at a given sequence position to test hypotheses about our model

- Understand how a neuron can be characterized in terms of its input and output weights

Probing Across Layers

The probe's inputs are accumulated in the residual stream over the six layers - the residual stream is the sum of the output of each previous head and neuron. We can therefore analyse which previous model components most contribute to the overall probe computation, and use this to identify the end of the world model computing circuit.

Let's analyse move 20 in game 1, where we can see that the probe has perfect accuracy after layer 6.

layer = 6

game_index = 1

move = 20

utils.plot_board_values(

focus_states[game_index, move],

text=focus_legal_moves_annotation[game_index][move],

title=f"Focus game #{game_index}, board after move {move}",

width=400,

height=400,

)

plot_probe_outputs(focus_cache, linear_probe, layer, game_index, move, title=f"Probe outputs (layer {layer})")

Click to see the expected output

We now plot the contributions of the attention and MLP layers to the my_probe direction. Strikingly, we see that the MLP layers are important for the vertical stripe that we just taken by the opponent, but that most of the rest seems to be done by the attention layers.

Exercise - compute attn and mlp contributions

Below, you should define attn_contributions and mlp_contributions. You should do this by taking the batched dot product of the vectors written to the residual stream in each layer (from layer 0 to layer layer inclusive), and the probe direction "my vs their" which you computed earlier (i.e. my_probe).

Note, we're looking for the marginal contribution to the probe direction from each of our components, not the accumulated residual stream. This is because we want to see which components have a strong effect on the output.

Hint - what activation names to use?

You should be using attn_out and mlp_out.

Calculating each of these two contributions will require taking an einsum with the activations and your probe.

Hint - what dimensions to multiply over?

my_probe has shape (d_model=512, rows=8, cols=8). You should multiply the residual stream at a given layer and my_probe over the d_model dimension (since your probe represents directions in the residual stream). Your output (for a given game index and move) will have shape (rows=8, cols=8), and will represent the amount by which that component of your model writes to the residual stream in the probe directions.

def calculate_attn_and_mlp_probe_score_contributions(

focus_cache: ActivationCache,

probe: Float[Tensor, "d_model rows cols"],

layer: int,

game_index: int,

move: int,

) -> tuple[Float[Tensor, "layers rows cols"], Float[Tensor, "layers rows cols"]]:

# YOUR CODE HERE - define `attn_contributions` and `mlp_contributions` using the cache & probe

return (attn_contributions, mlp_contributions)

layer = 6

attn_contributions, mlp_contributions = calculate_attn_and_mlp_probe_score_contributions(

focus_cache, my_probe, layer, game_index, move

)

utils.plot_board_values(

mlp_contributions,

title=f"MLP Contributions to my vs their (game #{game_index}, move {move})",

board_titles=[f"Layer {i}" for i in range(layer + 1)],

width=1400,

height=340,

)

utils.plot_board_values(

attn_contributions,

title=f"Attn Contributions to my vs their (game #{game_index}, move {move})",

board_titles=[f"Layer {i}" for i in range(layer + 1)],

width=1400,

height=340,

)

Click to see the expected output

Solution

def calculate_attn_and_mlp_probe_score_contributions(

focus_cache: ActivationCache,

probe: Float[Tensor, "d_model rows cols"],

layer: int,

game_index: int,

move: int,

) -> tuple[Float[Tensor, "layers rows cols"], Float[Tensor, "layers rows cols"]]:

attn_contributions = einops.einsum(

t.stack([focus_cache["attn_out", l][game_index, move] for l in range(layer + 1)]),

probe,

"layers d_model, d_model rows cols -> layers rows cols",

)

mlp_contributions = einops.einsum(

t.stack([focus_cache["mlp_out", l][game_index, move] for l in range(layer + 1)]),

probe,

"layers d_model, d_model rows cols -> layers rows cols",

)

return (attn_contributions, mlp_contributions)

Next, you should return (and plot) overall probe scores (i.e. from the accumulated residual stream by the end of layer layer). The code should be similar to the code you wrote immediately above, except you're taking the value at the residual stream up to and including layer layer, rather than the MLP or attention contributions.

def calculate_accumulated_probe_score(

focus_cache: ActivationCache,

probe: Float[Tensor, "d_model rows cols"],

layer: int,

game_index: int,

move: int,

) -> Float[Tensor, "layers rows cols"]:

# YOUR CODE HERE - define `attn_contributions` and `mlp_contributions` using the cache & probe

return residual_stream_score

residual_stream_score = calculate_accumulated_probe_score(focus_cache, my_probe, layer, game_index, move)

utils.plot_board_values(

residual_stream_score,

title=f"Residual stream probe values for 'my vs their' (game #{game_index}, move {move})",

board_titles=[f"Layer {i}" for i in range(layer + 1)],

width=1400,

height=340,

)

Click to see the expected output

Solution

def calculate_accumulated_probe_score(

focus_cache: ActivationCache,

probe: Float[Tensor, "d_model rows cols"],

layer: int,

game_index: int,

move: int,

) -> Float[Tensor, "layers rows cols"]:

residual_stream_score = einops.einsum(

t.stack([focus_cache["resid_post", l][game_index, move] for l in range(layer + 1)]),

probe,

"layer d_model, d_model rows cols -> layer rows cols",

)

return residual_stream_score

Exercise - repeat this for the "blank" probe

Make exactly the same plots, but using blank_probe instead of my_probe. What do you notice, and why?

# YOUR CODE HERE - repeat the results for `blank_probe`, and interpret them

Click to see the expected output

Solution code

attn_contributions, mlp_contributions = calculate_attn_and_mlp_probe_score_contributions(

focus_cache, blank_probe, layer, game_index, move

)

utils.plot_board_values(

mlp_contributions,

title=f"MLP Contributions to blank probe (game #{game_index}, move {move})",

board_titles=[f"Layer {i}" for i in range(layer + 1)],

width=1400,

height=340,

)

utils.plot_board_values(

attn_contributions,

title=f"Attn Contributions to blank probe (game #{game_index}, move {move})",

board_titles=[f"Layer {i}" for i in range(layer + 1)],

width=1400,

height=340,

)

residual_stream_score = calculate_accumulated_probe_score(focus_cache, blank_probe, layer, game_index, move)

utils.plot_board_values(

residual_stream_score,

title=f"Residual stream probe values for 'blank' (game #{game_index}, move {move})",

board_titles=[f"Layer {i}" for i in range(layer + 1)],

width=1400,

height=340,

)

Discussion

The algorithm "is this cell blank or not?" is pretty easy to implement - you just need to check if that cell has been played at some point in the game. Unlike telling whether a cell is black or white, this doesn't require an understanding of the piece-flipping rules.

The model seems to have a pretty good understanding of this past the zeroth attention layer, or at least it has all the pieces to understand that (even the larger magnitude contribution comes from e.g. the later MLP layers).

Reading off neuron weights

Another cool consequence of having a linear probe is having an interpretable set of directions in the residual stream. This means that we can read off the meaning of any neuron's input and output weights, in terms of the set of directions given by the probe.

Let's start with neuron L5N1393, which seemed interesting from my initial investigations.

Firstly, we'll compute the normalized version of the probes (normalization happens over the d_model dimension, i.e. blank_probe_normalized has shape (d_model, row, col) and the [:, i, j]-th entry is the residual stream probe direction fort the i, j-th cell in the board).

# Scale the probes down to be unit norm per cell

blank_probe_normalised = blank_probe / blank_probe.norm(dim=0, keepdim=True)

my_probe_normalised = my_probe / my_probe.norm(dim=0, keepdim=True)

# Set the center blank probes to 0, since they're never blank so the probe is meaningless

blank_probe_normalised[:, [3, 3, 4, 4], [3, 4, 3, 4]] = 0.0

Exercise - calculate neuron input weights

The function calculate_neuron_input_weights below takes layer and neuron. It should return a tensor of shape (row, col), where the [i, j]-th entry is the projection of this neuron's input weights onto the probe direction corresponding to the i, j-th cell in the board.

The function calculate_neuron_output_weights is very similar, but returns the projection of the neuron's output weights onto the probe direction.

Recall that, when we talk about a neuron's input and output weights, we're referring to the following decomposition:

where $x$ is a vector in the residual stream, $W^{in}$ is the input weight matrix, $W^{out}$ is the output weight matrix, $f$ is the activation function, and $\sum_n$ represents a sum over neurons.

You'll first write the helper function get_w_in and get_w_out, which returns the (normalized) vectors $W^{in}_{[:, n]}$ and $W^{out}_{[n, :]}$ for a given neuron. Then, you'll implement calculate_neuron_input_weights using this helper function.

Why do we normalize before projecting onto the probe direction? The reason we do this is because we don't care about the scale factor - you could double the magnitude of the output vector and half that of the corresponding input vector, and (ignoring biases) the result would be the same. Instead, we care about how much the input direction of our model's weights aligns with the probe direction we found in the residual stream. The fact that we've also normalized our probes means that we'll be plotting the cosine similarity of vectors.

Note - remember to use clone() and detach() if you're indexing into a model's weights and performing operations on it, when necessary. You use clone() because you don't want to modify the model's weights, and detach() because you don't want to compute gradients through the model's weights.

def get_w_in(

model: HookedTransformer,

layer: int,

neuron: int,

normalize: bool = False,

) -> Float[Tensor, "d_model"]:

"""

Returns the input weights for the given neuron.

If normalize is True, the weight is normalized to unit norm.

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

def get_w_out(

model: HookedTransformer,

layer: int,

neuron: int,

normalize: bool = False,

) -> Float[Tensor, "d_model"]:

"""

Returns the output weights for the given neuron.

If normalize is True, the weight is normalized to unit norm.

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

def calculate_neuron_input_weights(

model: HookedTransformer, probe: Float[Tensor, "d_model row col"], layer: int, neuron: int

) -> Float[Tensor, "rows cols"]:

"""

Returns tensor of the input weights for the given neuron, at each square on the board, projected

along the corresponding probe directions.

Assume probe directions are normalized. You should also normalize the model weights.

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

def calculate_neuron_output_weights(

model: HookedTransformer, probe: Float[Tensor, "d_model row col"], layer: int, neuron: int

) -> Float[Tensor, "rows cols"]:

"""

Returns tensor of the output weights for the given neuron, at each square on the board,

projected along the corresponding probe directions.

Assume probe directions are normalized. You should also normalize the model weights.

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

tests.test_calculate_neuron_input_weights(calculate_neuron_input_weights, model)

tests.test_calculate_neuron_output_weights(calculate_neuron_output_weights, model)

Solution

def get_w_in(

model: HookedTransformer,

layer: int,

neuron: int,

normalize: bool = False,

) -> Float[Tensor, "d_model"]:

"""

Returns the input weights for the given neuron.

If normalize is True, the weight is normalized to unit norm.

"""

w_in = model.W_in[layer, :, neuron].detach().clone()

if normalize:

w_in /= w_in.norm(dim=0, keepdim=True)

return w_in

def get_w_out(

model: HookedTransformer,

layer: int,

neuron: int,

normalize: bool = False,

) -> Float[Tensor, "d_model"]:

"""

Returns the output weights for the given neuron.

If normalize is True, the weight is normalized to unit norm.

"""

w_out = model.W_out[layer, neuron, :].detach().clone()

if normalize:

w_out /= w_out.norm(dim=0, keepdim=True)

return w_out

def calculate_neuron_input_weights(

model: HookedTransformer, probe: Float[Tensor, "d_model row col"], layer: int, neuron: int

) -> Float[Tensor, "rows cols"]:

"""

Returns tensor of the input weights for the given neuron, at each square on the board, projected

along the corresponding probe directions.

Assume probe directions are normalized. You should also normalize the model weights.

"""

w_in = get_w_in(model, layer, neuron, normalize=True)

return einops.einsum(w_in, probe, "d_model, d_model row col -> row col")

def calculate_neuron_output_weights(

model: HookedTransformer, probe: Float[Tensor, "d_model row col"], layer: int, neuron: int

) -> Float[Tensor, "rows cols"]:

"""

Returns tensor of the output weights for the given neuron, at each square on the board,

projected along the corresponding probe directions.

Assume probe directions are normalized. You should also normalize the model weights.

"""

w_out = get_w_out(model, layer, neuron, normalize=True)

return einops.einsum(w_out, probe, "d_model, d_model row col -> row col")

Now, let's examine neuron 1393 in more detail. Can you interpret what it's doing?

layer = 5

neuron = 1393

w_in_L5N1393_blank = calculate_neuron_input_weights(model, blank_probe_normalised, layer, neuron)

w_in_L5N1393_my = calculate_neuron_input_weights(model, my_probe_normalised, layer, neuron)

utils.plot_board_values(

t.stack([w_in_L5N1393_blank, w_in_L5N1393_my]),

title=f"Input weights in terms of the probe for neuron L{layer}N{neuron}",

board_titles=["Blank In", "My In"],

width=650,

height=380,

)

Click to see the expected output

Answer - what this neuron is doing

It seems to represent (C0==BLANK) & (D1==THEIRS) & (E2==MINE) - in other words, it fires strongest when all three of these conditions hold.

This is useful for the model, because if all three of these conditions hold, then C0 is a legal move (because it flips D1).

Exercise - test your hypothesis (output behaviour)

The plots above are evidence about the neuron's input behaviour (i.e. what causes it to fire), but we haven't tested its output behaviour (i.e. the effect it has when it fires) to see if it's in line with our hypothesis. You should make a particular plot to test your hypothesis about the neuron, using the plot_board_values function - we'll also leave it as an exercise to figure out what plot you should make!

# YOUR CODE HERE - create a plot to test your prediction

Click to see the expected output

Answer - what plot you should make

You should expect that this neuron fires to predict C0 is legal. In other words, when you map its output weights through the unembedding matrix, the values should be large for C0 and small for the other cells. You can test this by taking the output weights, mapping them through the unembedding, then plotting the result in an 8x8 square.

The name for this is direct logit attribution, or DLA. This is the standard way we study the direct effect of components that write to the residual stream (i.e. ignoring the paths that go through intermediate components).

Solution (code for plot)

Run the code below to create the plot - you should find that the neuron does boost the logit for C0 when it fires. Interestingly, there's also a positive logit effect on the cell D1. We'll look at this a bit deeper later on in the exercises, when we take a deeper dive into DLA.

# Get neuron output weights' cos sim with unembedding

w_out_L5N1393 = get_w_out(model, layer, neuron, normalize=True)

W_U_normalized = model.W_U[:, 1:] / model.W_U[:, 1:].norm(dim=0, keepdim=True) # normalize, slice off logits for "pass"

cos_sim = w_out_L5N1393 @ W_U_normalized # shape (60,)

# Turn into a (rows, cols) tensor, using indexing

cos_sim_rearranged = t.zeros((8, 8), device=device)

cos_sim_rearranged.flatten()[ALL_SQUARES] = cos_sim

# Plot results

utils.plot_board_values(

cos_sim_rearranged,

title=f"Cosine sim of neuron L{layer}N{neuron} with W<sub>U</sub> directions",

width=450,

height=380,

)

Note - you can also choose not to normalize weights; this will show you the output weights in the unembedding basis, rather than the cosine similarity between neuron output weight & unembedding vectors. But the latter is more informative because we know that 1 is the maximum value (and we have an idea of what to expect - the expected absolute value of the cosine similarity of 2 randomly chosen vectors in ND space scales as 1/sqrt(N) (we omit the derivation), which means 1/sqrt(512) ≈ 0.04 - you can check this empirically if you'd like).

How much variance does the probe explain?

We can also look at what fraction of the neuron's input and output weights are captured by the probe (because the vector was scaled to have unit norm, looking at the squared norm of its projection gives us this answer).

We see that the input weights are well explained by this, while the output weights are only somewhat well explained by this.

w_in_L5N1393 = get_w_in(model, layer, neuron, normalize=True)

w_out_L5N1393 = get_w_out(model, layer, neuron, normalize=True)

U, S, Vh = t.svd(t.cat([my_probe.reshape(cfg.d_model, 64), blank_probe.reshape(cfg.d_model, 64)], dim=1))

# Remove the final four dimensions of U, as the 4 center cells are never blank and so the blank

# probe is meaningless there.

probe_space_basis = U[:, :-4]

print(f"Fraction of input weights in probe basis: {((w_in_L5N1393 @ probe_space_basis).pow(2).sum()):.4f}")

print(f"Fraction of output weights in probe basis: {((w_out_L5N1393 @ probe_space_basis).pow(2).sum()):.4f}")

Fraction of input weights in probe basis: 0.6818 Fraction of output weights in probe basis: 0.1633

Help - I don't understand what's going on here.

The concatenated probe directions collectively have rank 128, just 1/4 of the total model dimensionality d_model=512. For a randomly chosen vector, we might expect about 1/4 of its squared norm to lie in the span of these probe directions (or to phrase it a different way, we might expect the probe directions to explain about 1/4 of the vector's variance).

For the input weights, we see that this value is larger, i.e. the neuron seems to fire primarily in response to these probe directions (this agrees with what we saw above; that the neuron was detecting particular board states associated with these probe directions). For the output weights, this value is smaller, which would also make sense if our neuron was mainly predicting "C0 is legal" rather than itself being used to update the board state. In later exercises, you'll show that this is the case!

More neurons

Lets try this on the layer 3 neurons with the top standard deviation (of activations), and look at how their output weights affect the my probe direction.

layer = 3

top_neurons = focus_cache["post", layer][:, 3:-3].std(dim=[0, 1]).argsort(descending=True)[:10]

utils.plot_board_values(

t.stack([calculate_neuron_output_weights(model, blank_probe_normalised, layer, n) for n in top_neurons]),

title=f"Cosine sim of output weights and the 'blank color' probe for top layer {layer} neurons (by std dev)",

board_titles=[f"L{layer}N{n.item()}" for n in top_neurons],

width=1600,

height=360,

)

utils.plot_board_values(

t.stack([calculate_neuron_output_weights(model, my_probe_normalised, layer, n) for n in top_neurons]),

title=f"Cosine sim of output weights and the 'my color' probe for top layer {layer} neurons (by std dev)",

board_titles=[f"L{layer}N{n.item()}" for n in top_neurons],

width=1600,

height=360,

)

Click to see the expected output

Note - you can also experiment with kurtosis instead, which is a measure of the tail extremity of our distribution. This might help you find more neurons which activate sparsely (with signficiant outlier values) rather than just identifying neurons with a good mix of both small and large values (for more on why sparsity might tend to correlate with interpretability, see the material in this chapter on sparse autoencoders!).

Use this dropdown to get some code to implement kurtosis

def kurtosis(tensor: Tensor, reduced_axes, fisher=True):

"""

Computes the kurtosis of a tensor over specified dimensions.

"""

return (

((tensor - tensor.mean(dim=reduced_axes, keepdim=True)) / tensor.std(dim=reduced_axes, keepdim=True)) ** 4

).mean(dim=reduced_axes, keepdim=False) - fisher * 3

top_layer_3_neurons = einops.reduce(

focus_cache["post", layer][:, 3:-3], "game move neuron -> neuron", reduction=kurtosis

).argsort(descending=True)[:10]

We can also try plotting the top neurons for layer 4:

layer = 4

top_neurons = focus_cache["post", layer][:, 3:-3].std(dim=[0, 1]).argsort(descending=True)[:10]

utils.plot_board_values(

t.stack([calculate_neuron_output_weights(model, blank_probe_normalised, layer, n) for n in top_neurons]),

title=f"Cosine sim of output weights and the 'blank color' probe for top layer {layer} neurons (by std dev)",

board_titles=[f"L{layer}N{n.item()}" for n in top_neurons],

width=1600,

height=360,

)

utils.plot_board_values(

t.stack([calculate_neuron_output_weights(model, my_probe_normalised, layer, n) for n in top_neurons]),

title=f"Cosine sim of output weights and the 'my color' probe for top layer {layer} neurons (by std dev)",

board_titles=[f"L{layer}N{n.item()}" for n in top_neurons],

width=1600,

height=360,

)

Click to see the expected output

Why do all the top layer 4 neurons have such striking results, with almost perfect alignment with one of the blank probe directions (and very low alignment with the "my color" probe directions)?

A cell can only be legal to play in if it is blank (obviously). Since calculating blankness is easy (you just check whether a move was played), the model should be able to do this in a single layer - these are the neurons that we see above.

Question - if this is true, then what observation should we expect when we compare the neuron output weights to the unembedding weights?

Think about this before you read on.

Answer

If this is true, then we should expect the cosine similarity of output weights and the unembedding weights to exhibit the same heatmap pattern as we see above.

In other words, these neurons which are firing strongly on blank cells are also directly writing to the residual stream, having their output used in the unembedding to increase the logit score for the blank cells which they are detecting.

We'll test this out, using the same method of plotting the direct logit attribution as you should have used for the exercise "test your hypothesis" above.

layer = 4

top_neurons = focus_cache["post", layer][:, 3:-3].std(dim=[0, 1]).argsort(descending=True)[:10]

w_out = t.stack([get_w_out(model, layer, neuron, normalize=True) for neuron in top_neurons])

# Get neuron output weights' cos sim with unembedding

W_U_normalized = model.W_U[:, 1:] / model.W_U[:, 1:].norm(dim=0, keepdim=True) # normalize, slice off logits for "pass"

cos_sim = w_out @ W_U_normalized

# Turn into a tensor, using indexing

cos_sim_rearranged = t.zeros((10, 8, 8), device=device)

cos_sim_rearranged.flatten(1, -1)[:, ALL_SQUARES] = cos_sim

# Plot results

utils.plot_board_values(

cos_sim_rearranged,

title=f"Cosine sim of top neurons with W<sub>U</sub> directions (layer {layer})",

board_titles=[f"L{layer}N{n.item()}" for n in top_neurons],

width=1500,

height=320,

)

Click to see the expected output

Great! We've validated our hypothesis that the neurons in this layer are directly computing "blankness" and feeding this output directly into the unembedding, in order to raise the logit score for blank cells (since being blank is necessary for being legal to play in).

In section 3️⃣, we'll do more of this kind of direct logit attribution.

Question - if you try plotting the top layer 4 neurons by kurtosis, you won't find these "blank detecting" neurons (even though kurtosis seems to give better results for layer 3). Why do you think this is?

Sorting by kurtosis is best at finding outliers. Sorting by std dev will find you neurons with good variability / spread, i.e. a good mix of small and large values. This latter description better describes the blank detecting neurons, because they'll be bimodal (off if the square is blank, on if it's occupied - and both of these groups are nontrivially sized).

Recap of this section

We did the following:

- Defined helper functions

get_w_in,get_w_outwhich returned particular MLP weight vectors for a given neuron. - Defined functions

calculate_neuron_input_weightsandcalculate_neuron_output_weightswhich returned the projection of a neuron's input and output weights onto the directions of a given probe (e.g.my_probeorblank_probe). - Discovered that some neurons have very interpretable input weights, for example:

- After comparing the input weights of

L5N1393to the probe directions, we found that it was detecting a particular diagonal line of blank-theirs-mine, since this indicates that the blank square is legal.- This is interesting, and not necessarily something we could have predicted beforehand.

- We also looked at the logit lens for this neuron, and found that it was boosting the logit for the square that would be legal if this pattern was present.

- After looking at the input weights of some layer 4 neurons, we found that they were detecting whether a square was blank (since this is necessary for legality), and their output weights seemed to be directly used in the embedding to increase log probs for those blank squares.

- This is not as interesting and probably something we could have predicted, because the "check if cell" is blank operation is pretty easy.

- After comparing the input weights of

Activation Patching

A valuable technique for tracking down the action of various circuits is activation patching. This was first introduced in David Bau and Kevin Meng's excellent ROME paper, there called causal tracing.

The setup of activation patching is to take two runs of the model on two different inputs, the clean run and the corrupted run. The clean run outputs the correct answer and the corrupted run does not. The key idea is that we give the model the corrupted input, but then intervene on a specific activation and patch in the corresponding activation from the clean run (ie replace the corrupted activation with the clean activation), and then continue the run. And we then measure how much the output has updated towards the correct answer.

By carefully choosing clean and corrupted inputs that differ in one key detail, we can isolate which model components capture and depend on this detail.

The ability to localise is a key move in mechanistic interpretability - if the computation is diffuse and spread across the entire model, it is likely much harder to form a clean mechanistic story for what's going on. But if we can identify precisely which parts of the model matter, we can then zoom in and determine what they represent and how they connect up with each other, and ultimately reverse engineer the underlying circuit that they represent.

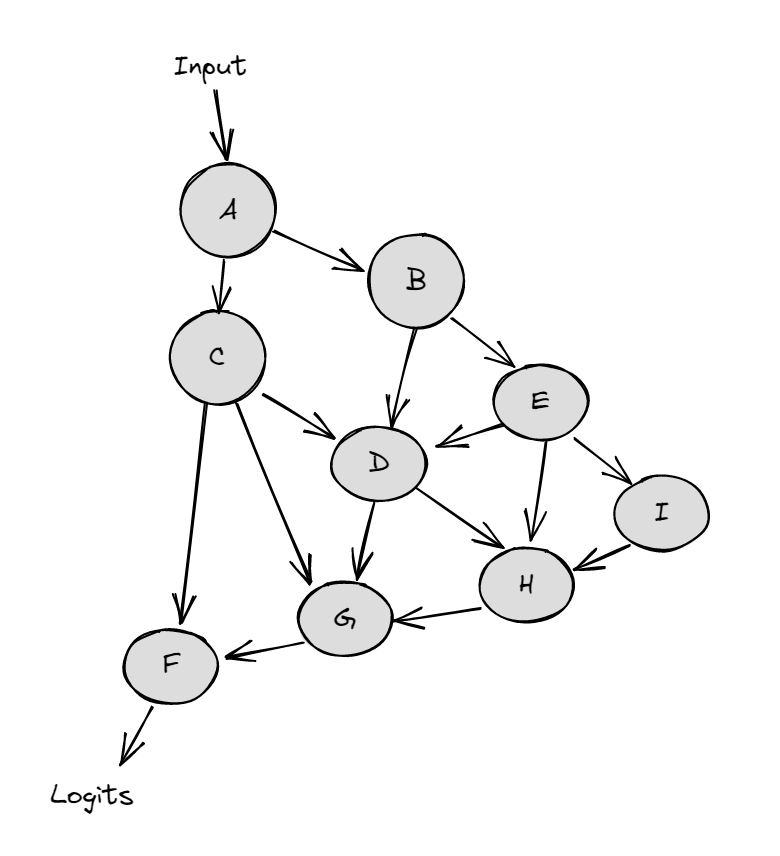

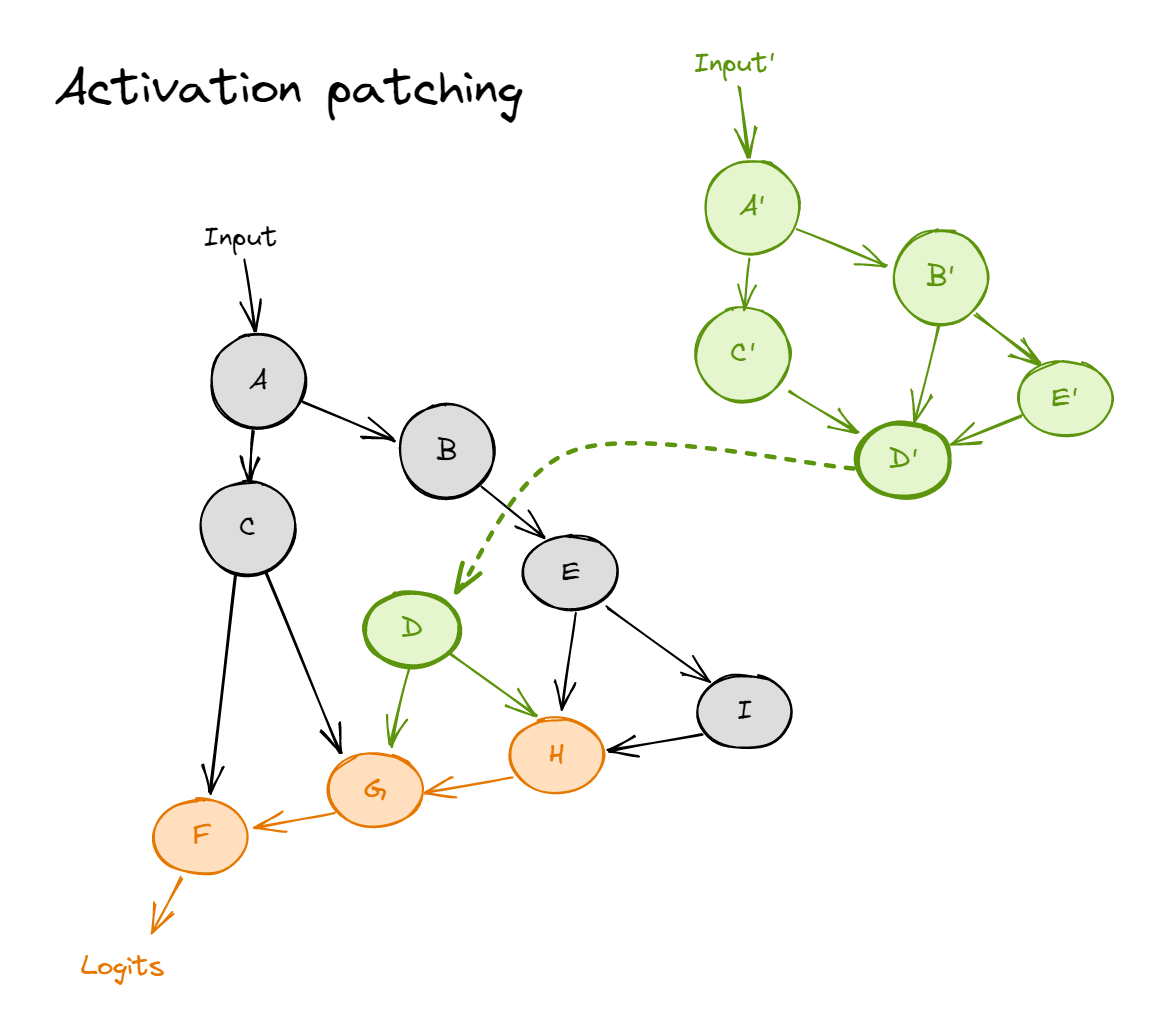

The diagrams below demonstrate activation patching on an abstract neural network (the nodes represent activations, and the arrows between them are weight connections).

A regular forward pass on the clean input looks like:

And activation patching from a corrupted input (green) into a forward pass for the clean input (black) looks like:

where the dotted line represents patching in a value (i.e. during the forward pass on the clean input, we replace node $D$ with the value it takes on the corrupted input). Nodes $H$, $G$ and $F$ are colored orange, to represent that they now follow a distribution which is not the same as clean or corrupted.

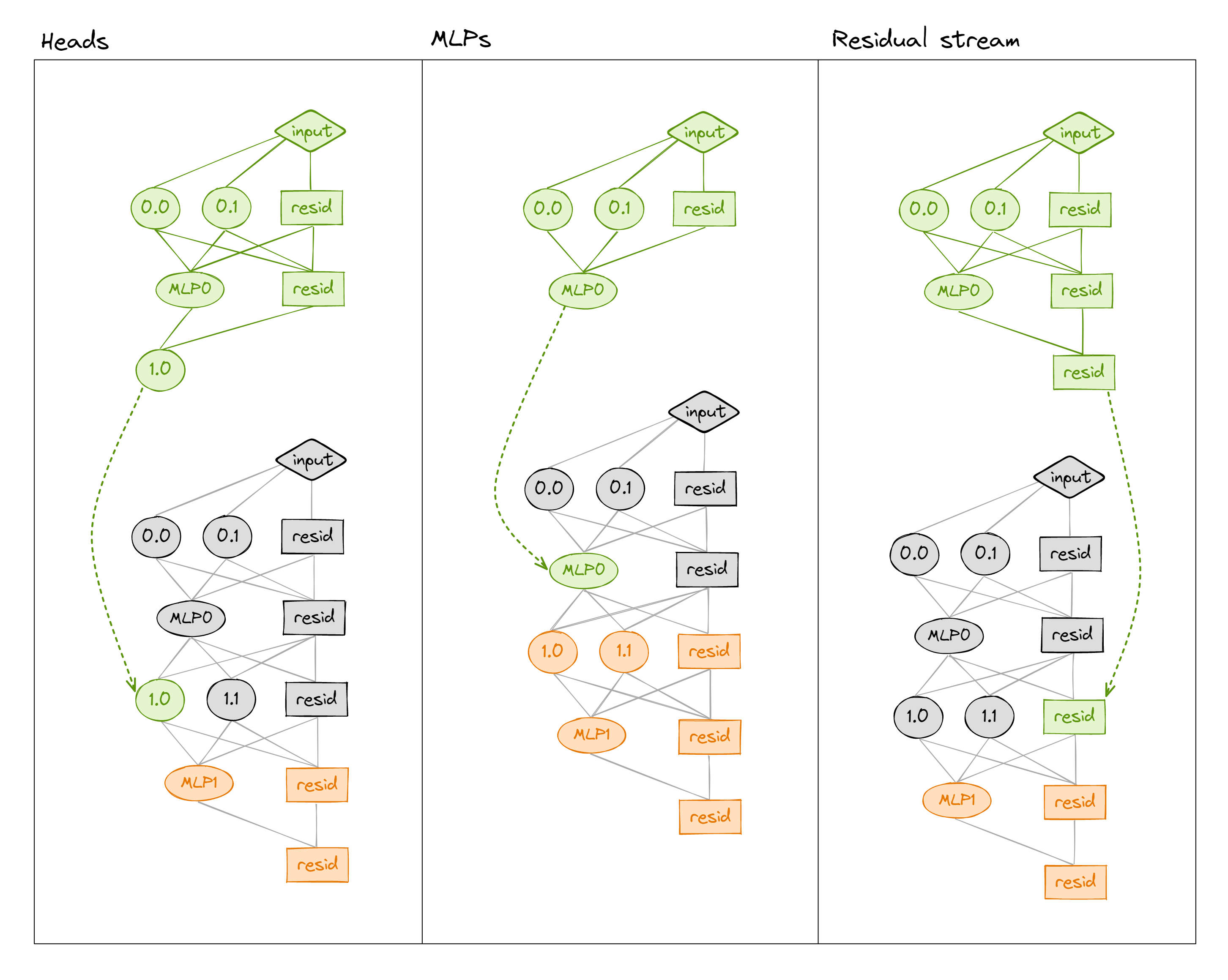

We can patch into a transformer in many different ways (e.g. values of the residual stream, the MLP, or attention heads' output - see below). We can also get even more granular by patching at particular sequence positions (not shown in diagram).

Setting up our patching

Before we patch, we need to decide what our clean and corrupted datasets will be, and create a metric for evaluating a set of logits.

Setting up clean and corrupted moves that result in similar games is non-trivial, so here we take a game and just change the most recent move from E0 to C0. This turns F0 (as a move for white to play) from legal to illegal, so let's make that logit our patching metric.

It also makes sense to have the metric be a linear function of the logit difference. This is enough to uniquely specify a metric.

First, we can plot the original and corrupted boards, to visualize this:

cell_r = 5

cell_c = 4

print(f"Flipping the color of cell {'ABCDEFGH'[cell_r]}{cell_c}")

board = utils.OthelloBoardState()

board.update(focus_games_square[game_index, : move + 1].tolist())

valid_moves = board.get_valid_moves()

flipped_board = copy.deepcopy(board)

flipped_board.state[cell_r, cell_c] *= -1

flipped_legal_moves = flipped_board.get_valid_moves()

newly_legal = [utils.square_to_label(move) for move in flipped_legal_moves if move not in valid_moves]

newly_illegal = [utils.square_to_label(move) for move in valid_moves if move not in flipped_legal_moves]

print("newly_legal", newly_legal)

print("newly_illegal", newly_illegal)

Flipping the color of cell F4 newly_legal [] newly_illegal ['C6']

game_index = 4

move = 20

# Get original & corrupted games (as token IDs & ints)

original_game_id = focus_games_id[game_index, : move + 1]

corrupted_game_id = original_game_id.clone()

corrupted_game_id[-1] = utils.label_to_id("C0")

original_game_square = t.tensor([utils.id_to_square(original_game_id)])

corrupted_game_square = t.tensor([utils.id_to_square(corrupted_game_id)])

original_state, original_legal_moves, original_legal_moves_annotation = get_board_states_and_legal_moves(

original_game_square

)

corrupted_state, corrupted_legal_moves, corrupted_legal_moves_annotation = get_board_states_and_legal_moves(

corrupted_game_square

)

utils.plot_board_values(

t.stack([original_state[move], corrupted_state[move]]),

text=[original_legal_moves_annotation[move], corrupted_legal_moves_annotation[move]],

title="Focus game states",

board_titles=["Original game (black plays E0)", "Corrupted game (black plays C0)"],

width=650,

height=380,

)

Click to see the expected output

Next, let's get our logits & cache for both games:

original_logits, original_cache = model.run_with_cache(original_game_id)

corrupted_logits, corrupted_cache = model.run_with_cache(corrupted_game_id)

original_log_probs = original_logits.log_softmax(dim=-1)

corrupted_log_probs = corrupted_logits.log_softmax(dim=-1)

Exercise - create a patching metric

Finally, we'll create a patching metric. This is a function we'll apply to our output logits, in order to measure how much they've changed (in some important way) from their clean values.

We want our patching metric to satisfy the following conditions:

- Should have value one when the logits are the same as in the clean distribution.

- Should have value zero when the logits are the same as in the corrupted distribution.

- Note - we sometimes use the opposite convention. Either might be justified, depending on the context. Here, you should think of a value of 1 meaning "100% of performance is preserved", and 0 as "performance is gone".

- Should be a linear function of the log probs.

- Important note - this is not the same as being a linear function of the logits. Can you see why?

- Should just be a function of the logits for the

F0token, at the final game move (since this is the only move that changes between clean and corrupted).- Note - you can index into the

d_vocabdimension of logits using thef0_indexvariable defined below.

- Note - you can index into the

This should be enough for you to uniquely define your patching metric. Also, note that it should return a scalar tensor (this is important for the transformerlens patching functions to work).

F0_index = utils.label_to_id("F0")

original_F0_log_prob = original_log_probs[0, -1, F0_index]

corrupted_F0_log_prob = corrupted_log_probs[0, -1, F0_index]

print("Check that the model predicts F0 is legal in original game & illegal in corrupted game:")

print(f"Clean log prob: {original_F0_log_prob.item():.2f}")

print(f"Corrupted log prob: {corrupted_F0_log_prob.item():.2f}\n")

def patching_metric(patched_logits: Float[Tensor, "batch seq d_vocab"]) -> Float[Tensor, ""]:

"""

Function of patched logits, calibrated so that it equals 0 when performance is same as on

corrupted input, and 1 when performance is same as on original input.

Should be linear function of the logits for the F0 token at the final move.

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

tests.test_patching_metric(patching_metric, original_log_probs, corrupted_log_probs)

Solution

def patching_metric(patched_logits: Float[Tensor, "batch seq d_vocab"]) -> Float[Tensor, ""]:

"""

Function of patched logits, calibrated so that it equals 0 when performance is same as on

corrupted input, and 1 when performance is same as on original input.

Should be linear function of the logits for the F0 token at the final move.

"""

patched_log_probs = patched_logits.log_softmax(dim=-1)

return (patched_log_probs[0, -1, F0_index] - corrupted_F0_log_prob) / (original_F0_log_prob - corrupted_F0_log_prob)

Exercise - write a patching function

Below, you should fill in the functions patch_attn_layer_output and patch_mlp_layer_output.

To do this, you'll have to use TransformerLens hooks. A quick refresher on how they work:

- Hook functions take two compulsory arguments:

tensor(a PyTorch tensor of the model's activations at this hookpoint)hook(aHookPointobject, which has helper propertyhook.nameand methodhook.layer())

- The function

model.run_with_hookstakes arguments:- The tokens to run (as first argument)

fwd_hooks- a list of(hook_name, hook_fn)tuples. Remember that you can useget_act_nameto get hook names.

Tips:

- It's good practice to have model.reset_hooks() at the start of functions which add and run hooks. This is because sometimes hooks fail to be removed (if they cause an error while running). There's nothing more frustrating than fixing a hook error only to get the same error message, not realising that you've failed to clear the broken hook!

- The HookPoint object has method .layer() and attribute .name which can be useful in your hook functions.

def patch_final_move_output(

activation: Float[Tensor, "batch seq d_model"],

hook: HookPoint,

clean_cache: ActivationCache,

) -> Float[Tensor, "batch seq d_model"]:

"""

Hook function which patches activations at the final sequence position.

Note, we only need to patch in the final sequence position, because the prior moves in the clean

and corrupted input are identical (and this is an autoregressive model).

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

def get_act_patch_resid_pre(

model: HookedTransformer,

corrupted_input: Float[Tensor, "batch pos"],

clean_cache: ActivationCache,

patching_metric: Callable[[Float[Tensor, "batch seq d_model"]], Float[Tensor, ""]],

) -> Float[Tensor, "2 n_layers"]:

"""

Returns an array of results corresponding to the results of patching at each (attn_out, mlp_out)

for all layers in the model.

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

patching_results = get_act_patch_resid_pre(model, corrupted_game_id, original_cache, patching_metric)

pd.options.plotting.backend = "plotly"

pd.DataFrame(to_numpy(patching_results.T), columns=["attn", "mlp"]).plot.line(

title="Layer Output Patching Effect on F0 Log Prob",

width=700,

labels={"value": "Patching Effect", "index": "Layer"},

).show()

Click to see the expected output

Spoiler - what results you should get

We can see that most layers just don't matter! But MLP0, MLP5, MLP6 and Attn7 do! My next steps would be to get more fine grained and to patch in individual neurons and see how far I can zoom in on why those layers matter - ideally at the level of understanding how these neurons compose with each other and the changed the embedding, using the fact that most of the model just doesn't matter here. And then to compare this data to the above techniques for understanding neurons. If you want to go off and explore this, that would be a great exercise at this point (or to return to at the end of the exercises).

It's not surprising that the attention layers are fairly unimportant - attention specialises in moving information between token positions, we've only changed the information at the current position! (Attention does have the ability to operate on the current position, but that's not the main thing it does).

Solution

def patch_final_move_output(

activation: Float[Tensor, "batch seq d_model"],

hook: HookPoint,

clean_cache: ActivationCache,

) -> Float[Tensor, "batch seq d_model"]:

"""

Hook function which patches activations at the final sequence position.

Note, we only need to patch in the final sequence position, because the prior moves in the clean

and corrupted input are identical (and this is an autoregressive model).

"""

activation[0, -1, :] = clean_cache[hook.name][0, -1, :]

return activation

def get_act_patch_resid_pre(

model: HookedTransformer,

corrupted_input: Float[Tensor, "batch pos"],

clean_cache: ActivationCache,

patching_metric: Callable[[Float[Tensor, "batch seq d_model"]], Float[Tensor, ""]],

) -> Float[Tensor, "2 n_layers"]:

"""

Returns an array of results corresponding to the results of patching at each (attn_out, mlp_out)

for all layers in the model.

"""

model.reset_hooks()

results = t.zeros(2, model.cfg.n_layers, device=device, dtype=t.float32)

hook_fn = partial(patch_final_move_output, clean_cache=clean_cache)

for i, activation in enumerate(["attn_out", "mlp_out"]):

for layer in tqdm(range(model.cfg.n_layers)):

patched_logits = model.run_with_hooks(

corrupted_input,

fwd_hooks=[(get_act_name(activation, layer), hook_fn)],

)

results[i, layer] = patching_metric(patched_logits)

return results

Recap of this section

We did the following:

- Learned how activation patching worked.

- Constructed the following datasets for patching:

- Clean distribution = unaltered game,

- Corrupted distribution = game with a single move flipped (changing th legality of a square),

- Looked at the effect on patching at the output of attention and MLP layers to see which ones changed the output significantly.

- We found a handful of the MLP layers, and the final attention layer, mattered.

- Attention layers mostly not mattering was unsurprising, since attention's main job is to move around information rather than operate on it.

- If we wanted, we could get more granular at this point, and explore which neurons in these layers had a significant effect.

- We found a handful of the MLP layers, and the final attention layer, mattered.