☆ Bonus

Learning Objectives

- Use your understanding of how the model works to generate adversarial examples.

- Take deeper dives into specific anomalous features of the model.

Investigating the bracket transformer

Here, we have a few bonus exercises which build on the previous content (e.g. having you examine different parts of the model, or use your understanding of how the model works to generate adversarial examples).

This final section is less guided, although the suggested exercises are similar in flavour to the previous section.

Learning objctives

- Use your understanding of how the model works to generate adversarial examples.

- Take deeper dives into specific anomalous features of the model.

The main bonus exercise we recommend you try is adversarial attacks. You'll need to read the first section of the detecting anywhere-negative failures bonus exercise to get an idea for how the other half of the classification circuit works, but once you understand this you can jump ahead to the adversarial attacks section.

Detecting anywhere-negative failures

When we looked at our grid of attention patterns, we saw that not only did the first query token pay approximately uniform attention to all tokens following it, but so did most of the other tokens (to lesser degrees). This means that we can write the vector written to position $i$ (for general $i\geq 1$) as:

where $n_L^{(i)}$ and $n_R^{(i)}$ are the number of left and right brackets respectively in the substring formed from brackets[i: n] (i.e. this matches our definition of $n_L$ and $n_R$ when $i=1$).

Given what we've seen so far (that sequence position 1 stores tally information for all the brackets in the sequence), we can guess that each sequence position stores a similar tally, and is used to determine whether the substring consisting of all brackets to the right of this one has any elevation failures (i.e. making sure the total number of right brackets is at least as great as the total number of left brackets - recall it's this way around because our model learned the equally valid right-to-left solution).

Recall that the destination token only determines how much to pay attention to the source; the vector that is moved from the source to destination conditional on attention being paid to it is the same for all destination tokens. So the result about left-paren and right-paren vectors having cosine similarity of -1 also holds for all later sequence positions.

Head 2.1 turns out to be the head for detecting anywhere-negative failures (i.e. it detects whether any sequence brackets[i: n] has strictly more right than left parentheses, and writes to the residual stream in the unbalanced direction if this is the case). Can you find evidence for this behaviour?

One way you could investigate this is to construct a parens string which "goes negative" at some points, and look at the attention probabilities for head 2.0 at destination position 0. Does it attend most strongly to those source tokens where the bracket goes negative, and is the corresponding vector written to the residual stream one which points in the unbalanced direction?

You could also look at the inputs to head 2.1, just like we did for head 2.0. Which components are most important, and can you guess why?

Answer

You should find that the MLPs are important inputs into head 2.1. This makes sense, because earlier we saw that the MLPs were converting tally information $(n_L - \alpha n_R)$ into the boolean information $(n_L = n_R)$ at sequence position 1. Since MLPs act the same on all sequence positions, it's reasonable to guess that they're storing the boolean information $(n_L^{(i)} > n_R^{(i)})$ at each sequence position $i$, which is what we need to detect anywhere-negative failures.

Adversarial attacks

Our model gets around 1 in a ten thousand examples wrong on the dataset we've been using. Armed with our understanding of the model, can we find a misclassified input by hand? I recommend stopping reading now and trying your hand at applying what you've learned so far to find a misclassified sequence. If this doesn't work, look at a few hints.

adversarial_examples = ["()", "(())", "))"]

# YOUR CODE HERE - update the `adversarial_examples` list, to find adversarial examples!

m = max(len(ex) for ex in adversarial_examples)

toks = tokenizer.tokenize(adversarial_examples)

probs = model(toks)[:, 0].softmax(-1)[:, 1]

print(

"\n".join(

[f"{ex:{m}} -> {p:.4%} balanced confidence" for (ex, p) in zip(adversarial_examples, probs)]

)

)

Hint 1

What's up with those weird patchy bits in the bottom-right corner of the attention patterns? Can we exploit this?

Read the next hint for some more specific directions.

Hint 2

We observed that each left bracket attended approximately uniformly to each of the tokens to its right, and used this to detect elevation failures at any point. We also know that this approximately uniform pattern breaks down around query positions 27-31.

With this in mind, what kind of "just barely" unbalanced bracket string could we construct that would get classified as balanced by the model?

Read the next hint for a suggested type of bracket string.

Hint 3

We want to construct a string that has a negative elevation at some point, but is balanced everywhere else. We can do this by using a sequence of the form A)(B, where A and B are balanced substrings. The positions of the open paren next to the B will thus be the only position in the whole sequence on which the elevation drops below zero, and it will drop just to -1.

Read the next hint to get ideas for what A and B should be (the clue is in the attention pattern plot!).

Hint 4

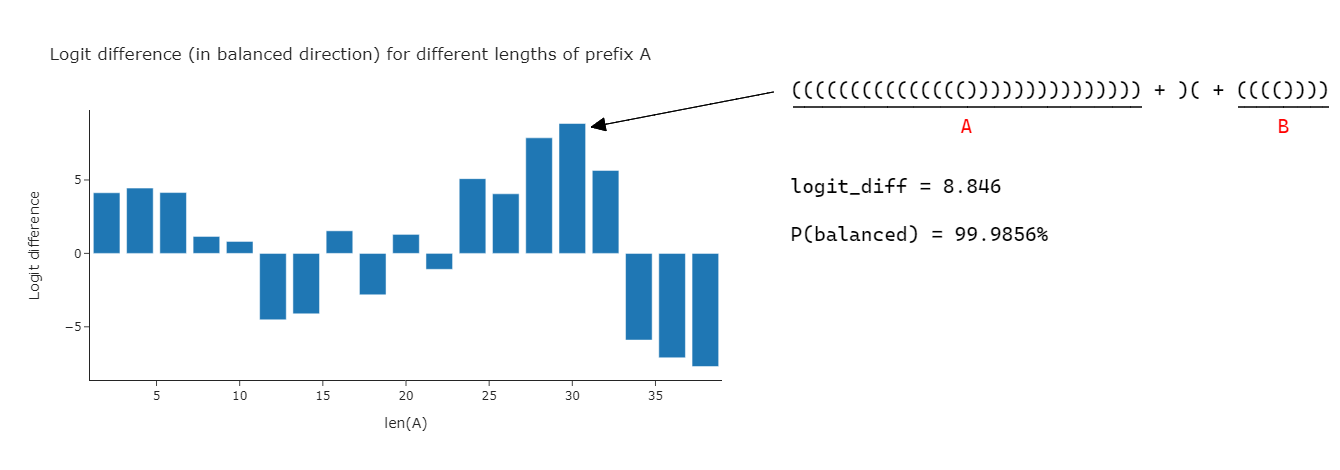

From the attention pattern plot, we can see that left parens in the range 27-31 attend bizarrely strongly to the tokens at position 38-40. This means that, if there is a negative elevation in or after the range 27-31, then the left bracket that should be detecting this negative elevation might miscount. In particular, if B = ((...)), this left bracket might heavily count the right brackets at the end, and less heavily weight the left brackets at the start of B, thus this left bracket might "think" that the sequence is balanced when it actually isn't.

Solution (for best currently-known advex)

Choose A and B to each be a sequence of (((...))) terms with length $i$ and $38-i$ respectively (it makes sense to choose A like this also, because want the sequence to have maximal positive elevation everywhere except the single position where it's negative). Then, maximize over $i = 2, 4, ...\,$. Unsurprisingly given the observations in the previous hint, we find that the best adversarial examples (all with balanced probability of above 98%) are $i=24, 26, 28, 30, 32$. The best of these is $i=30$, which gets 99.9856% balanced confidence.

def tallest_balanced_bracket(length: int) -> str:

return "".join(["(" for _ in range(length)] + [")" for _ in range(length)])

example = tallest_balanced_bracket(15) + ")(" + tallest_balanced_bracket(4)

Dealing with early closing parens

We mentioned that our model deals with early closing parens differently. One of our components in particular is responsible for classifying any sequence that starts with a closed paren as unbalnced - can you find the component that does this?

Hint

It'll have to be one of the attention heads, since these are the only things which can move information from sequence position 1 to position 0 (and the failure mode we're trying to detect is when the sequence has a closed paren in position 1).

Which of your attention heads was previously observed to move information from position 1 to position 0?

Can you plot the outputs of this component when there is a closed paren at first position? Can you prove that this component is responsible for this behavior, and show exactly how it happens?

Suggested capstone projects

Try more algorithmic problems

Interpreting toy models is a good way to increase your confidence working with TransformerLens and basic interpretability methods. It's maybe not the most exciting category of open problems in mechanistic interpretability, but can still be a useful exercise - and sometimes it can lead to interesting new insights about how interpretability tools can be used.

If you're feeling like it, you can try to hop onto LeetCode and pick a suitable problem (we recommend the "Easy" section) to train a transformer and interpret its output. Here are a few suggestions to get you started (some of these were taken from LeetCode, others from Neel Nanda's open problems post). They're listed approximately from easier to harder, although this is just a guess since I haven't personally interpreted these. Note, there are ways you could make any of these problems easier or harder with modifications - I've included some ideas inline.

- Calculating sequences with a Fibonacci-style recurrence relation (i.e. predicting the next element from the previous two)

- Search Insert Position - an easier version would be when the target is always guaranteed to be in the list (you also wouldn't need to worry about sorting in this case). The version without this guarantee is a very different problem, and would be much harder

- Is Subsequence - you should start with subsequences of length 1 (in which case this problem is pretty similar to the easier version of the previous problem), and work up from there

- Majority Element - you can try playing around with the data generation process to change the difficulty, e.g. sequences where there is no guarantee on the frequency of the majority element (i.e. you're just looking for the token which appears more than any other token) would be much harder

- Number of Equivalent Domino Pairs - you could restrict this problem to very short lists of dominos to make it easier (e.g. start with just 2 dominos!)

- Longest Substring Without Repeating Characters

- Isomorphic Strings - you could make it simpler by only allowing the first string to have duplicate characters, or by restricting the string length / vocabulary size

- Plus One - you might want to look at the "sum of numbers" algorithmic problem before trying this, and/or the grokking exercises in this chapter. Understanding this problem well might actually help you build up to interpreting the "sum of numbers" problem (I haven't done this, so it's very possible you could come up with a better interpretation of that monthly problem than mine, since I didn't go super deep into the carrying mechanism)

- Predicting permutations, i.e. predicting the last 3 tokens of the 12-token sequence

(17 3 11) (17 1 13) (11 2 4) (11 4 2)(i.e. the model has to learn what permutation function is being applied to the first group to get the second group, and then apply that permutation to the third group to correctly predict the fourth group). Note, this problem might require 3 layers to solve - can you see why? - Train models for automata tasks and interpret them - do your results match the theory?

- Predicting the output to simple code functions. E.g. predicting the

1 2 4text in the following sequence (which could obviously be made harder with some obvious modifications, e.g. adding more variable definitions so the model has to attend back to the right one):

a = 1 2 3

a[2] = 4

a -> 1 2 4

- Graph theory problems like this. You might have to get creative with the input format when training transformers on tasks like this!

Note, ARENA runs a monthly algorithmic problems sequence, and you can get ideas from looking at past problems from this sequence. You can also use these repos to get some sample code for building & training a trnasformer on a toy model, and constructing a dataset for your particular problem.

Suggested paper replications

Causal Scrubbing

Causal scrubbing is an algorithm developed by Redwood Research, which tries to create an automated metric for dweciding whether a computational subgraph corresponds to a circuit. Some reading on this:

- Neel's dynalist notes (short)

- Causal Scrubbing: a method for rigorously testing interpretability hypotheses (full LessWrong post describing the algorithm)

- You can also read Redwood's full sequence here, where they mention applying it to the paren balancer

- Practical Pitfalls of Causal Scrubbing

Can you write the causal scrubbing algorithm, and use it to replicate their results? You might want to start with induction heads before applying it to the bracket classifier.

This might be a good replication for you if:

- You like high levels of rigour, rather than the more exploratory-style work we've largely focused on so far

- You enjoyed these exercises, and feel like you have a good understanding of the kinds of circuits implemented by this bracket classifier

- (Ideally) you've done some investigation of the "detecting anywhere negative failures" bonus exercise suggested above

A circuit for Python docstrings in a 4-layer attention-only transformer

This work was produced as part of the SERI ML Alignment Theory Scholars Program (Winter 2022) under the supervision of Neel Nanda. Similar to how the IOI paper searched for in some sense the simplest kind of circuit which required 3 layers, this work was looking for the simplest kind of circuit which required 4 layers. The task they investigated was the docstring task - can you predict parameters in the right order, in situations like this (the code was generated by choosing random words):

def port(self, load, size, files, last):

|||oil column piece

:param load: crime population

:param size: unit dark

:param

The token that follows should be files, and just like in the case of IOI we can deeply analyze how the transformer solves this task. Unlike IOI, we're looking at a 4-layer transformer which was trained on code (not GPT2-Small), which makes a lot of the analysis cleaner (even though the circuit has more levels of composition than IOI does).

For an extra challenge, rather than replicating the authors' results, you can try and perform this investigation yourself, without seeing what tools the authors of the paper used! Most will be similar to the ones you've used in the exercises so far.

This might be a good replication for you if:

- You enjoyed most/all sections of these exercises, and want to practice using the tools you learned in a different context - specifically, a model which is less algorithmic and might not have as crisp a circuit as the bracket transformer

- You'd prefer to do something with a bit more of a focus on real language models, but still don't want to go all the way up to models as large as GPT2-Small

Note, this replication is closer to [1.3] Indirect Object Identification than to these exercises. If you've got time before finishing this chapter then we recommend you try these exercises first, since they'll be very helpful for giving you a set of tools which are more suitable for working with large models.