1️⃣ Bracket classifier

Learning Objectives

- Understand how transformers can be used for classification.

- Understand how to implement specific kinds of transformer behaviour (e.g. masking of padding tokens) via permanent hooks in TransformerLens.

- Start thinking about the kinds of algorithmic solutions a transformer is likely to find for problems such as these, given its inductive biases.

This section describes how transformers can be used for classification, and the details of how this works in TransformerLens (using permanent hooks). It also takes you through the exercise of hand-writing a solution to the balanced brackets problem.

This section mainly just lays the groundwork; it is very light on content.

One of the many behaviors that a large language model learns is the ability to tell if a sequence of nested parentheses is balanced. For example, (())(), ()(), and (()()) are balanced sequences, while )(), ())(), and ((()((()))) are not.

In training, text containing balanced parentheses is much more common than text with imbalanced parentheses - particularly, source code scraped from GitHub is mostly valid syntactically. A pretraining objective like "predict the next token" thus incentivizes the model to learn that a close parenthesis is more likely when the sequence is unbalanced, and very unlikely if the sequence is currently balanced.

Some questions we'd like to be able to answer are:

- How robust is this behavior? On what inputs does it fail and why?

- How does this behavior generalize out of distribution? For example, can it handle nesting depths or sequence lengths not seen in training?

If we treat the model as a black box function and only consider the input/output pairs that it produces, then we're very limited in what we can guarantee about the behavior, even if we use a lot of compute to check many inputs. This motivates interpretibility: by digging into the internals, can we obtain insight into these questions? If the model is not robust, can we directly find adversarial examples that cause it to confidently predict the wrong thing? Let's find out!

Today's Toy Model

Today we'll study a small transformer that is trained to only classify whether a sequence of parentheses is balanced or not. It's small so we can run experiments quickly, but big enough to perform well on the task. The weights and architecture are provided for you.

Causal vs bidirectional attention

The key difference between this and the GPT-style models you will have implemented already is the attention mechanism.

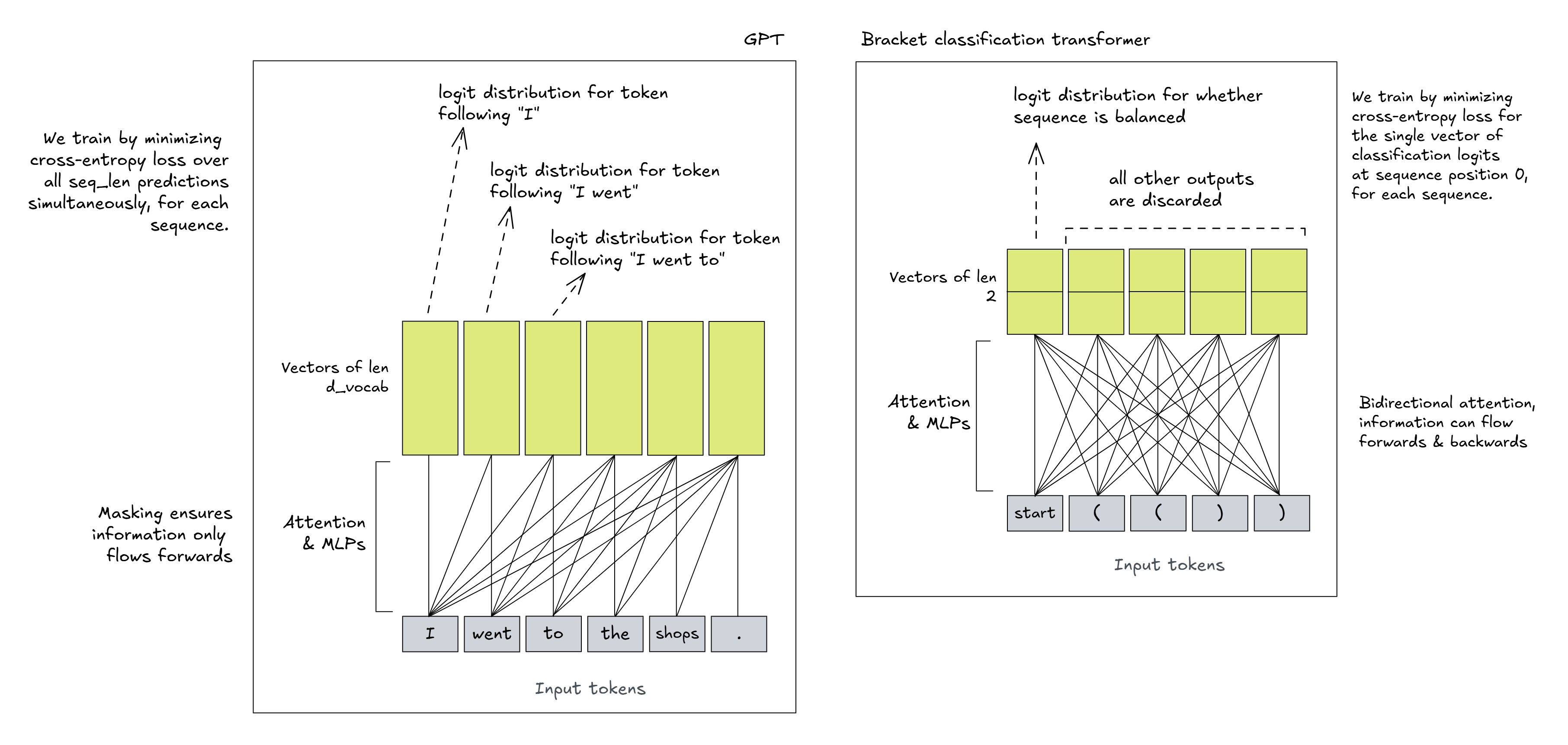

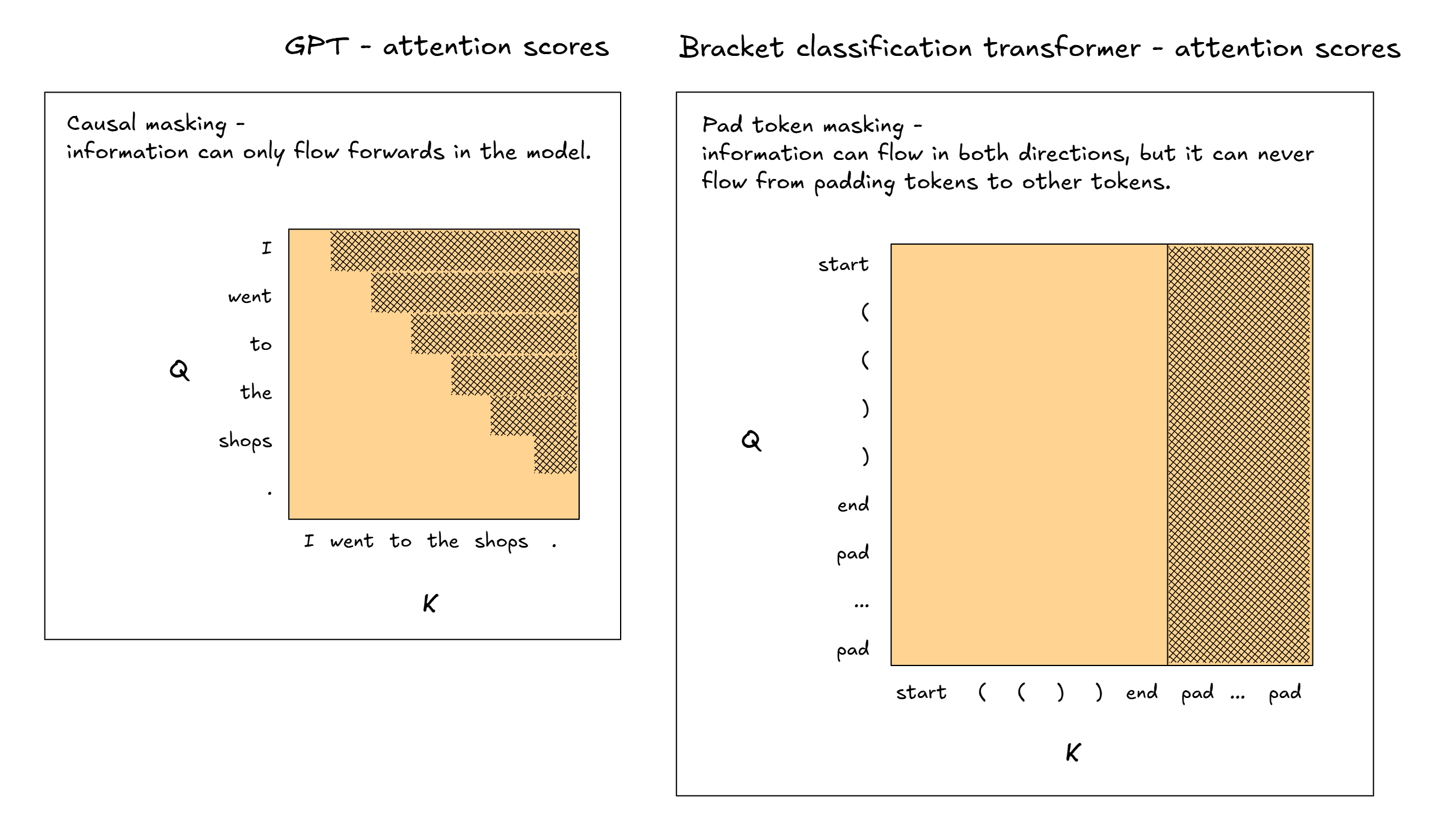

GPT uses causal attention, where the attention scores get masked wherever the source token comes after the destination token. This means that information can only flow forwards in a model, never backwards (which is how we can train our model in parallel - our model's output is a series of distributions over the next token, where each distribution is only able to use information from the tokens that came before). This model uses bidirectional attention, where the attention scores aren't masked based on the relative positions of the source and destination tokens. This means that information can flow in both directions, and the model can use information from the future to predict the past.

Using transformers for classification

GPT is trained via gradient descent on the cross-entropy loss between its predictions for the next token and the actual next tokens. Models designed to perform classification are trained in a very similar way, but instead of outputting probability distributions over the next token, they output a distribution over class labels. We do this by having an unembedding matrix of size [d_model, num_classifications], and only using a single sequence position (usually the 0th position) to represent our classification probabilities.

Below is a schematic to compare the model architectures and how they're used:

Note that, just because the outputs at all other sequence positions are discarded, doesn't mean those sequence positions aren't useful. They will almost certainly be the sites of important intermediate calculations. But it does mean that the model will always have to move the information from those positions to the 0th position in order for the information to be used for classification.

A note on softmax

For each bracket sequence, our (important) output is a vector of two values: (l0, l1), representing the model's logit distribution over (unbalanced, balanced). Our model was trained by minimizing the cross-entropy loss between these logits and the true labels. Interestingly, since logits are translation invariant, the only value we actually care about is the difference between our logits, l0 - l1. This is the model's log likelihood ratio of the sequence being unbalanced vs balanced. Later on, we'll be able to use this logit_diff to perform logit attribution in our model.

Masking padding tokens

The image on the top-right is actually slightly incomplete. It doesn't show how our model handles sequences of differing lengths. After all, during training we need to have all sequences be of the same length so we can batch them together in a single tensor. The model manages this via two new tokens: the end token and the padding token.

The end token goes at the end of every bracket sequence, and then we add padding tokens to the end until the sequence is up to some fixed length. For instance, this model was trained on bracket sequences of up to length 40, so if we wanted to classify the bracket string (()) then we would pad it to the length-42 sequence:

[start] + ( + ( + ) + ) + [end] + [pad] + [pad] + ... + [pad]

When we calculate the attention scores, we mask them at all (query, key) positions where the key is a padding token. This makes sure that information doesn't flow from padding tokens to other tokens in the sequence (just like how GPT's causal masking makes sure that information doesn't flow from future tokens to past tokens).

Note that the attention scores aren't masked when the query is a padding token and the key isn't. In theory, this means that information can be stored in the padding token positions. However, because the padding token key positions are always masked, this information can't flow back into the rest of the sequence, so it never affects the final output. (Also, note that if we masked query positions as well, we'd get numerical errors, since we'd be taking softmax across a row where every element is minus infinity, which is not well-defined!)

Aside on how this relates to BERT

This is all very similar to how the bidirectional transformer BERT works:

BERT has the[CLS] (classification) token rather than [start]; but it works exactly the same.

BERT has the [SEP] (separation) token rather than [end]; this has a similar function but also serves a special purpose when it is used in NSP (next sentence prediction).

If you're interested in reading more on this, you can check out [this link](https://albertauyeung.github.io/2020/06/19/bert-tokenization.html/).

We've implemented this type of masking for you, using TransformerLens's permanent hooks feature. We will discuss the details of this below (permanent hooks are a recent addition to TransformerLens which we havent' covered yet, and they're useful to understand).

Other details

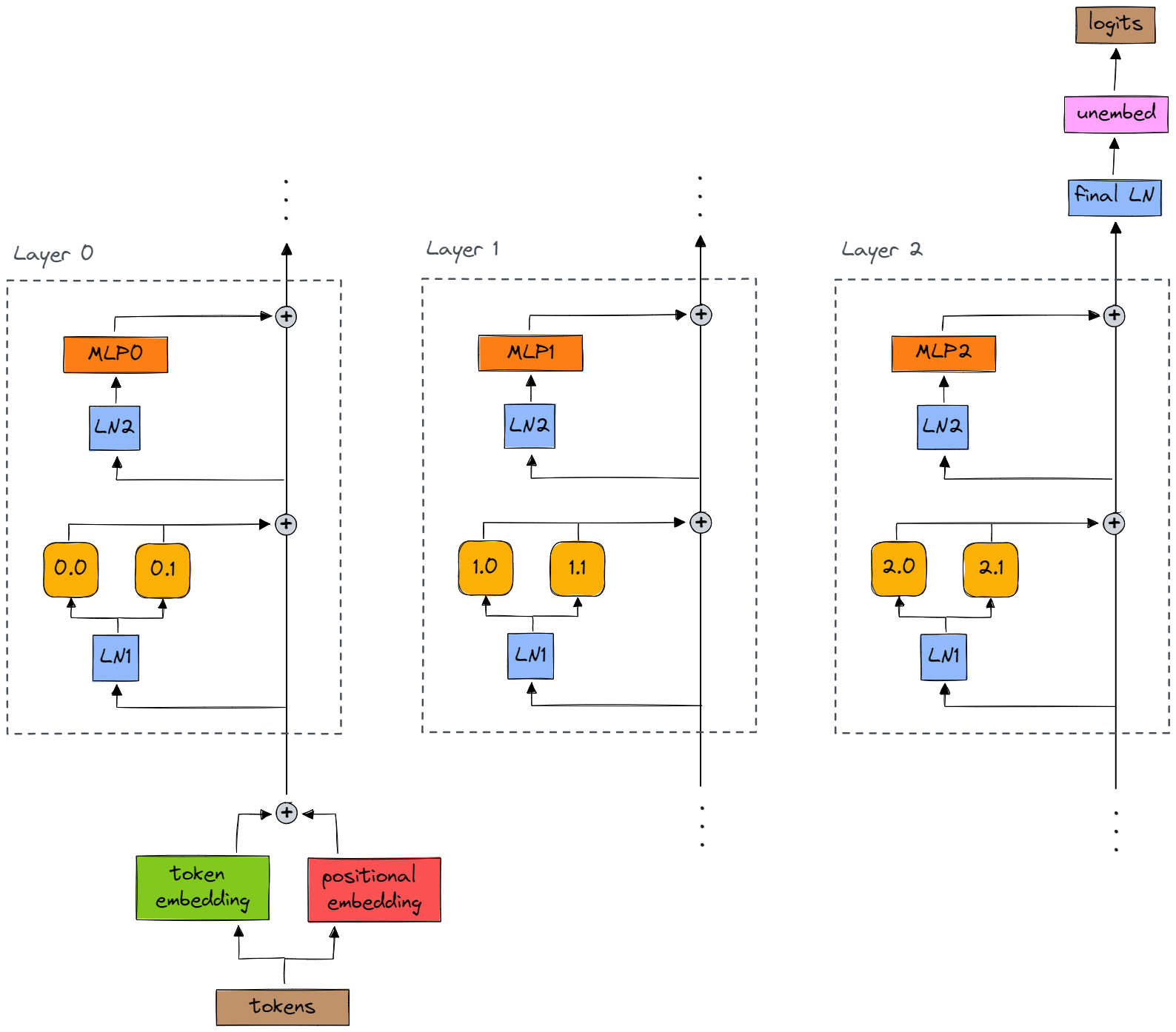

Here is a summary of all the relevant architectural details:

- Positional embeddings are sinusoidal (non-learned).

- It has

hidden_size(akad_model, akaembed_dim) of 56. - It has bidirectional attention, like BERT.

- It has 3 attention layers and 3 MLPs.

- Each attention layer has two heads, and each head has

headsize(akad_head) ofhidden_size / num_heads = 28. - The MLP hidden layer has 56 neurons (i.e. its linear layers are square matrices).

- The input of each attention layer and each MLP is first layernormed, like in GPT.

- There's a LayerNorm on the residual stream after all the attention layers and MLPs have been added into it (this is also like GPT).

- Our embedding matrix

W_Ehas five rows: one for each of the tokens[start],[pad],[end],(, and)(in that order). - Our unembedding matrix

W_Uhas two columns: one for each of the classesunbalancedandbalanced(in that order).- When running our model, we get output of shape

[batch, seq_len, 2], and we then take the[:, 0, :]slice to get the output for the[start]token (i.e. the classification logits). - We can then softmax to get our classification probabilities.

- When running our model, we get output of shape

- Activation function is

ReLU.

To refer to attention heads, we'll again use the shorthand layer.head where both layer and head are zero-indexed. So 2.1 is the second attention head (index 1) in the third layer (index 2).

Some useful diagrams

Here is a high-level diagram of your model's architecture:

Here is a link to a diagram of the archicture of a single model layer (which includes names of activations, as well as a list of useful methods for indexing into the model).

I'd recommend having both these images open in a different tab.

Defining the model

Here, we define the model according to the description we gave above.

VOCAB = "()"

cfg = HookedTransformerConfig(

n_ctx=42,

d_model=56,

d_head=28,

n_heads=2,

d_mlp=56,

n_layers=3,

attention_dir="bidirectional", # defaults to "causal"

act_fn="relu",

d_vocab=len(VOCAB) + 3, # plus 3 because of end and pad and start token

d_vocab_out=2, # 2 because we're doing binary classification

use_attn_result=True,

device=device,

use_hook_tokens=True,

)

model = HookedTransformer(cfg).eval()

state_dict = t.load(section_dir / "brackets_model_state_dict.pt", map_location=device)

model.load_state_dict(state_dict)

Tokenizer

There are only five tokens in our vocabulary: [start], [pad], [end], (, and ) in that order. See earlier sections for a reminder of what these tokens represent.

You have been given a tokenizer SimpleTokenizer("()") which will give you some basic functions. Try running the following to see what they do:

tokenizer = SimpleTokenizer("()")

# Examples of tokenization

# (the second one applies padding, since the sequences are of different lengths)

print(tokenizer.tokenize("()"))

print(tokenizer.tokenize(["()", "()()"]))

# Dictionaries mapping indices to tokens and vice versa

print(tokenizer.i_to_t)

print(tokenizer.t_to_i)

# Examples of decoding (all padding tokens are removed)

print(tokenizer.decode(t.tensor([[0, 3, 4, 2, 1, 1]])))

tensor([[0, 3, 4, 2]])

tensor([[0, 3, 4, 2, 1, 1],

[0, 3, 4, 3, 4, 2]])

{3: '(', 4: ')', 0: '[start]', 1: '[pad]', 2: '[end]'}

{'(': 3, ')': 4, '[start]': 0, '[pad]': 1, '[end]': 2}

['()']

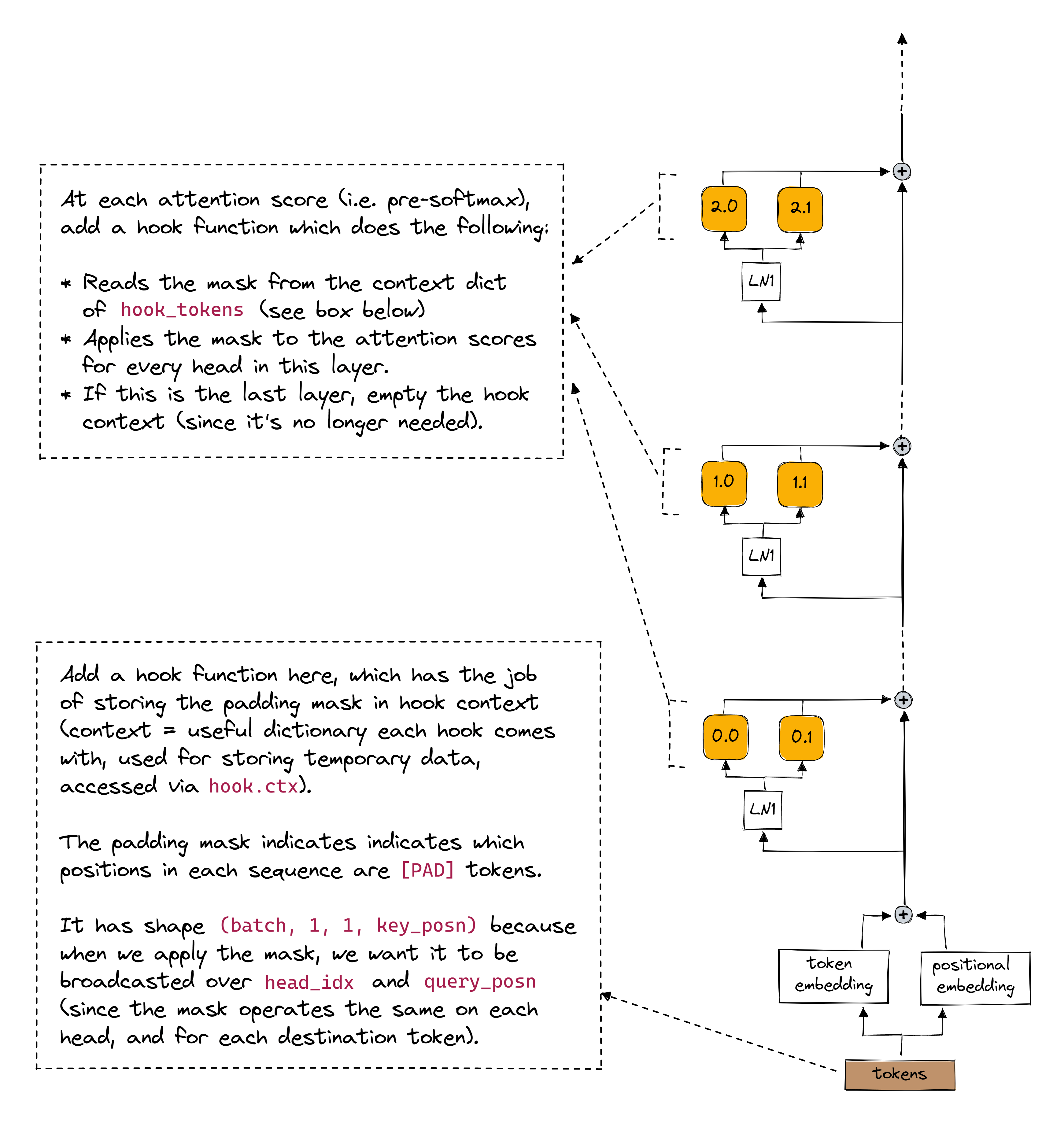

Implementing our masking

Now that we have the tokenizer, we can use it to write hooks that mask the padding tokens. If you understand how the padding works, then don't worry if you don't follow all the implementational details of this code.

Click to see a diagram explaining how this masking works (should help explain the code below)

def add_perma_hooks_to_mask_pad_tokens(

model: HookedTransformer, pad_token: int

) -> HookedTransformer:

# Hook which operates on the tokens, and stores a mask where tokens equal [pad]

def cache_padding_tokens_mask(tokens: Float[Tensor, "batch seq"], hook: HookPoint) -> None:

hook.ctx["padding_tokens_mask"] = einops.rearrange(tokens == pad_token, "b sK -> b 1 1 sK")

# Apply masking, by referencing the mask stored in the `hook_tokens` hook context

def apply_padding_tokens_mask(

attn_scores: Float[Tensor, "batch head seq_Q seq_K"],

hook: HookPoint,

) -> None:

attn_scores.masked_fill_(model.hook_dict["hook_tokens"].ctx["padding_tokens_mask"], -1e5)

if hook.layer() == model.cfg.n_layers - 1:

del model.hook_dict["hook_tokens"].ctx["padding_tokens_mask"]

# Add these hooks as permanent hooks (i.e. they aren't removed after functions like run_with_hooks)

for name, hook in model.hook_dict.items():

if name == "hook_tokens":

hook.add_perma_hook(cache_padding_tokens_mask)

elif name.endswith("attn_scores"):

hook.add_perma_hook(apply_padding_tokens_mask)

return model

model.reset_hooks(including_permanent=True)

model = add_perma_hooks_to_mask_pad_tokens(model, tokenizer.PAD_TOKEN)

Dataset

Each training example consists of [start], up to 40 parens, [end], and then as many [pad] as necessary.

In the dataset we're using, half the sequences are balanced, and half are unbalanced. Having an equal distribution is on purpose to make it easier for the model.

Remember to download the brackets_data.json file from this Google Drive link if you haven't already.

N_SAMPLES = 5000

with open(section_dir / "brackets_data.json") as f:

data_tuples = json.load(f)

print(f"loaded {len(data_tuples)} examples, using {N_SAMPLES}")

data_tuples = data_tuples[:N_SAMPLES]

data = BracketsDataset(data_tuples).to(device)

data_mini = BracketsDataset(data_tuples[:100]).to(device)

loaded 100000 examples, using 5000

You are encouraged to look at the code for BracketsDataset (scroll up to the setup code at the top - but make sure to not look to closely at the solutions!) to see what methods and properties the data object has.

Data visualisation

As is good practice, let's examine the dataset and plot the distribution of sequence lengths (e.g. as a histogram). What do you notice?

hist(

[len(x) for x, _ in data_tuples],

nbins=data.seq_length,

title="Sequence lengths of brackets in dataset",

labels={"x": "Seq len"},

)

Features of dataset

The most striking feature is that all bracket strings have even length. We constructed our dataset this way because if we had odd-length strings, the model would presumably have learned the heuristic "if the string is odd-length, it's unbalanced". This isn't hard to learn, and we want to focus on the more interesting question of how the transformer is learning the structure of bracket strings, rather than just their length.

Bonus exercise (optional) - can you describe an algorithm involving a single attention head which the model could use to distinguish between even and odd-length bracket strings?Answer

The algorithm might look like:

- QK circuit causes head to attend from seqpos=0 to the largest non-masked sequence position (e.g. we could have the key-query dot products of positional embeddings q[0] @ k[i] be a decreasing function of i = 0, 1, 2, ...)

- OV circuit maps the parity component of positional embeddings to a prediction, i.e. all odd positions would be mapped to an "unbalanced" prediction, and even positions to a "balanced" prediction

As an extra exercise, can you construct such a head by hand?

Now that we have all the pieces in place, we can try running our model on the data and generating some predictions.

# Define and tokenize examples

examples = ["()()", "(())", "))((", "()", "((()()()()))", "(()()()(()(())()", "()(()(((())())()))"]

labels = [True, True, False, True, True, False, True]

toks = tokenizer.tokenize(examples)

# Get output logits for the 0th sequence position (i.e. the [start] token)

logits = model(toks)[:, 0]

# Get the probabilities via softmax, then get the balanced probability (which is the second element)

prob_balanced = logits.softmax(-1)[:, 1]

# Display output

print(

"Model confidence:\n"

+ "\n".join(

[

f"{ex:18} : {prob:<8.4%} : label={int(label)}"

for ex, prob, label in zip(examples, prob_balanced, labels)

]

)

)

Model confidence: ()() : 99.9986% : label=1 (()) : 99.9989% : label=1 ))(( : 0.0005% : label=0 () : 99.9987% : label=1 ((()()()())) : 99.9987% : label=1 (()()()(()(())() : 0.0006% : label=0 ()(()(((())())())) : 99.9982% : label=1

We can also run our model on the whole dataset, and see how many brackets are correctly classified.

def run_model_on_data(

model: HookedTransformer, data: BracketsDataset, batch_size: int = 200

) -> Float[Tensor, "batch 2"]:

"""Return probability that each example is balanced"""

all_logits = []

for i in tqdm(range(0, len(data.strs), batch_size)):

toks = data.toks[i : i + batch_size]

logits = model(toks)[:, 0]

all_logits.append(logits)

all_logits = t.cat(all_logits)

assert all_logits.shape == (len(data), 2)

return all_logits

test_set = data

n_correct = (run_model_on_data(model, test_set).argmax(-1).bool() == test_set.isbal).sum()

print(f"\nModel got {n_correct} out of {len(data)} training examples correct!")

Model got 5000 out of 5000 training examples correct!

Algorithmic Solutions

Exercise - handwritten solution (for loop)

A nice property of using such a simple problem is we can write a correct solution by hand. Take a minute to implement this using a for loop and if statements.

def is_balanced_forloop(parens: str) -> bool:

"""

Return True if the parens are balanced.

Parens is just the ( and ) characters, no begin or end tokens.

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

for parens, expected in zip(examples, labels):

actual = is_balanced_forloop(parens)

assert expected == actual, f"{parens}: expected {expected} got {actual}"

print("All tests for `is_balanced_forloop` passed!")

Solution

def is_balanced_forloop(parens: str) -> bool:

"""

Return True if the parens are balanced.

Parens is just the ( and ) characters, no begin or end tokens.

"""

cumsum = 0

for paren in parens:

cumsum += 1 if paren == "(" else -1

if cumsum < 0:

return False

return cumsum == 0

Exercise - handwritten solution (vectorized)

A transformer has an inductive bias towards vectorized operations, because at each sequence position the same weights "execute", just on different data. So if we want to "think like a transformer", we want to get away from procedural for/if statements and think about what sorts of solutions can be represented in a small number of transformer weights.

Being able to represent a solutions in matrix weights is necessary, but not sufficient to show that a transformer could learn that solution through running SGD on some input data. It could be the case that some simple solution exists, but a different solution is an attractor when you start from random initialization and use current optimizer algorithms.

def is_balanced_vectorized(tokens: Float[Tensor, "seq_len"]) -> bool:

"""

Return True if the parens are balanced.

tokens is a vector which has start/pad/end indices (0/1/2) as well as left/right brackets (3/4)

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

for tokens, expected in zip(tokenizer.tokenize(examples), labels):

actual = is_balanced_vectorized(tokens)

assert expected == actual, f"{tokens}: expected {expected} got {actual}"

print("All tests for `is_balanced_vectorized` passed!")

Hint

One solution is to map begin, pad, and end tokens to zero, map open paren to 1 and close paren to -1. Then take the cumulative sum, and check the two conditions which are necessary and sufficient for the bracket string to be balanced.

Solution

def is_balanced_vectorized(tokens: Float[Tensor, "seq_len"]) -> bool:

"""

Return True if the parens are balanced.

tokens is a vector which has start/pad/end indices (0/1/2) as well as left/right brackets (3/4)

"""

# Convert start/end/padding tokens to zero, and left/right brackets to +1/-1

table = t.tensor([0, 0, 0, 1, -1])

change = table[tokens]

# Get altitude by taking cumulative sum

altitude = t.cumsum(change, -1)

# Check that the total elevation is zero and that there are no negative altitudes

no_total_elevation_failure = altitude[-1] == 0

no_negative_failure = altitude.min() >= 0

return (no_total_elevation_failure & no_negative_failure).item()

The Model's Solution

It turns out that the model solves the problem like this:

At each position i, the model looks at the slice starting at the current position and going to the end: seq[i:]. It then computes (count of closed parens minus count of open parens) for that slice to generate the output at that position.

We'll refer to this output as the "elevation" at i, or equivalently the elevation for each suffix seq[i:].

The sequence is imbalanced if one or both of the following is true:

elevation[0]is non-zeroany(elevation < 0)

For English readers, it's natural to process the sequence from left to right and think about prefix slices seq[:i] instead of suffixes, but the model is bidirectional and has no idea what English is. This model happened to learn the equally valid solution of going right-to-left.

We'll spend today inspecting different parts of the network to try to get a first-pass understanding of how various layers implement this algorithm. However, we'll also see that neural networks are complicated, even those trained for simple tasks, and we'll only be able to explore a minority of the pieces of the puzzle.