2️⃣ Understanding latents: a deeper dive

Learning Objectives

- Study feature splitting, and what it means for SAE training

- Use UMAPs and other dimensionality-reduction techniques to better understand SAE latent geometry

- Understand feature absorption, and how meta-SAEs might help us disentangle this problem (not implemented yet)

- Use the logit lens & techniques like token enrichment analysis to better understand & characterize SAE latents (not implemented yet)

- Take a deeper dive into automated interpretability, covering autointerp-based evals & patch scoping (not implemented yet)

Terminology note - in this context, we do say "feature splitting" and "feature absorption", because we're talking about how the underlying features of the data are split across different SAE latents. So it's the features themselves that are splitting, not the latents. Similarly, "feature absorption" describes a phenomenon of how the underlying features are distributed across different latents, so we don't call it "latent absorption".

Introduction

In this section, we'll take a deeper dive into some SAE topics which we didn't explore in the first section, and which aren't circuit related. Generally, these topics will fall into one of 2 categories:

- Understanding the relationship between SAE latents / their geometric structure (e.g. feature splitting & absorption)

- Zooming in to better understand the role of individual latents (e.g. with tools like logit lens & automated interpretability)

Both of these types of analysis can help us understand SAEs better. However, it's important to consider many different lines of evidence when working with SAEs, because individual pieces of evidence can often be misleading, or less useful than others. For example, some latents can often make a lot more sense if they're viewed as part of a group that split from a single latent in a narrower SAE, whereas other latents will be insufficiently important to appear in narrower SAEs. And some latents might seem very straightforward and interpretable when we apply automated interpretability to them, even though digging deeper reveals that the description would produce false negatives & misses out on important details.

At the end of this section, we'll suggest an open-ended exercise where you take a single latent in some SAE and try to understand it as deeply as possible, using all these different lines of evidence. We strongly recommend people attempt this exercise, as it's both a great way to practice both your skill at using all these different tools & methods, and a way of developing a more careful, skeptical research methodology when doing SAE interpretability (or interpretability in general).

Feature Splitting

Feature splitting is one especially interesting motif that was discovered early in the study of SAEs. From Anthropic's "Towards Monosemanticity" paper:

One striking thing about the features we’ve found is that they appear in clusters. For instance, we observed above multiple base64 features, multiple Arabic script features, and so on. We see more of these features as we increase the total number of learned sparse features, a phenomenon we refer to as feature splitting. As we go from 512 features in A/0 to 4,096 features in A/1 and to 16,384 features in A/2, the number of features specific to base64 contexts goes from 1 to 3 to many more.

They go on to analyze the feature splitting phenomenon in more detail by creating 2D UMAPs of the combined set of latents from their different SAEs. UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) is a dimension reduction technique that can be used for visualisation similarly to t-SNE, but also for general non-linear dimension reduction. Anthropic observed some interesting geometric structure in their UMAPs, which seem to correspond to semantic structure in the latent space of the model (in other words, latents that have similar meanings also have small angles between their dictionary vectors).

In the following exercises, we'll replicate some of these qualitative UMAP results, and try to build intuition for how the geometry of our latent space corresonds to closeness of latent interpretations.

First, let's load in our models & SAEs. We'll be using GPT2-Small, and a set of models trained by Joseph Bloom with a series of different widths (designed for the purpose of exploring feature splitting).

sae_release = "gpt2-small-res-jb-feature-splitting"

widths = [768 * (2**n) for n in range(7)] # Note, you can increase to 8 if it fits on your GPU

sae_ids = [f"blocks.8.hook_resid_pre_{width}" for width in widths]

splitting_saes = {

width: SAE.from_pretrained(sae_release, sae_id, device=str(device))[0]

for width, sae_id in zip(widths, sae_ids)

}

gpt2 = HookedSAETransformer.from_pretrained("gpt2-small", device=device)

To help you easily understand the results of your UMAPs, we'll also load in the autointerp descriptions for each SAE. Note that we've given you a function which drops duplicates, so we only get one description per latent.

def load_and_process_autointerp_dfs(width: int):

# Load in dataframe

release = get_pretrained_saes_directory()[sae_release]

neuronpedia_id = release.neuronpedia_id[f"blocks.8.hook_resid_pre_{width}"]

url = "https://www.neuronpedia.org/api/explanation/export?modelId={}&saeId={}".format(

*neuronpedia_id.split("/")

)

headers = {"Content-Type": "application/json"}

data = requests.get(url, headers=headers).json()

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Drop duplicate latent descriptions

df["index"] = df["index"].astype(int)

df = df.drop_duplicates(subset=["index"], keep="first").sort_values("index", ignore_index=True)

# Fill in missing latent descriptions with empty strings

full_index = pd.DataFrame({"index": range(width)})

df = full_index.merge(df, on="index", how="left")

df["description"] = df["description"].fillna("")

print(f"Loaded autointerp df for {width=}")

if (n_missing := (df["description"] == "").sum()) > 0:

print(f" Warning: {n_missing}/{len(df)} latents missing descriptions")

return df

autointerp_dfs = {width: load_and_process_autointerp_dfs(width) for width in widths}

display(autointerp_dfs[768].head())

Click to see the expected output

Exercise - study these SAEs

Use the neuronpedia page (or displaying inline latent dashboards using display_dashboard) to study the latents in these SAEs. Try to find examples of latent splitting between some pair of SAEs in this set. Do they seem similar to the examples of latent splitting from Anthropic's "Towards Monosemanticity" post?

Use this dropdown for a few ideas on how to approach this exercise

- You can start with a latent from the narrow SAE, and try to find latents in the wide SAE which also fire on the top activating examples of the narrow-SAE latent. - You can take a given sequence and pass it through the model & SAEs, and find latents which fire on both. - You can use autointerp descriptions: searching over the intersection of both the wide and the small SAE for latents which seem to match a particular description. (Note that you can use embedding similarity from e.g. [OpenAI's text embedding models](https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/embeddings) to find a set of autointerp descriptions which are similar to a given description)

Exercise - create UMAP

You should now fill in the function below, to create a UMAP of different SAEs. You can then run the cell to plot the results of your UMAP.

The code for specifying & fitting a UMAP is as follows:

umap = UMAP(

n_components=n_components,

n_neighbors=n_neighbors,

min_dist=min_dist,

metric="cosine",

)

umap_embedding = umap.fit_transform(values)

where values is a tensor (make sure to have on cpu not cuda) of shape (n_data, d) consisting of n_data separate vectors. The output is an array of shape (n_data, n_components) containing the UMAP coordinates of each vector. Note that this might take a while to run (up to about a minute), so don't worry if it's not immediate. If you like, you can test your function by editing it to only run on a small subset of the data (say, 100 latents), and then checking that the output looks sensible. Nowever, note that for our particular situation, the time taken for each UMAP should scale much slower than O(n_data ** 2), so it should be possible to create maps from any of the SAEs you'll be loading in this section.

If we're creating a 2D UMAP then you'll want to set n_components=2. The n_neighbors and min_dist arguments are hyperparameters of the UMAP algorithm, which control the trade off between local structure (how many neighbors each point has) and global structure (how far apart points are). You can see the UMAP docstrings for more on these. In the case of your 2D UMAP, you can use n_neighbors_visual and min_dist_visual as these arguments. See the next exercise for how the other arguments n_neighbors_cluster etc are used.

A final note - so that the plot is more interpretable, we've included the fields "top_token_strs" and "description" in the hoverdata. The former should be the top 10 boosted tokens for each latent (i.e. the largest values when you pass the decoder matrix through the model's unembedding). The latter should be the autointerp description, taken from the corresponding dataframe in autointerp_dfs which is defined for you in the code above. These are both recommended, but optional - if you don't want to bother with this, then you can comment the field out of the hoverdata argument in the plotting function.

import hdbscan

from umap import UMAP

def compute_sae_umap_data(

saes: dict[int, SAE],

autointerp_dfs: dict[int, pd.DataFrame],

sae_widths: list[int],

model: HookedSAETransformer,

n_neighbors_visual: int = 15,

min_dist_visual: float = 0.05,

find_clusters: bool = False,

n_neighbors_cluster: float = 15,

min_dist_cluster: float = 0.1,

min_cluster_size: int = 3,

batch_size: int = 1000,

) -> pd.DataFrame:

"""

This function will return a dataframe containing umap coordinates & other data (you can then use

this to create a plot using the code immediately below). The UMAP calculation is done over

multiple SAEs simultaneously, for comparison.

Expected dataframe columns:

sae_width: int

The width of the SAE that this latent belongs to

latent_idx: int

The index of the latent

umap_x: float

The x-coordinate of the latent in the UMAP embedding

umap_y: float

The y-coordinate of the latent in the UMAP embedding

autointerp: str

The autointerp description of this latent

top_token_strs_formatted: str

The top 10 tokens that the latent is activated by

Args:

saes: dict[int, SAE]

List of SAEs to use for the UMAP calculation

autointerp_dfs: dict[int, pd.DataFrame]

Dataframes containing autointerp descriptions for each SAE

sae_widths: list[int]

The widths of SAEs we'll be using for the UMAP calculation

model: HookedSAETransformer

The model which all the SAEs should be attached to

n_neighbors_visual: int

The number of neighbors to consider for the UMAP embedding for the visual plot

min_dist_visual: float

The minimum distance between points in the UMAP embedding for the visual plot

n_neighbors_cluster: int

The number of neighbors to consider for the UMAP embedding for the cluster plot

min_dist_cluster: float

The minimum distance between points in the UMAP embedding for the cluster plot

min_cluster_size: int

The minimum number of points in a cluster.

batch_size: int

Number of latents to process at once, for logits

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

# This took about 40s to run for me in Colab Pro+, 80s on my VastAI A100 remote machine

expansion_factors = [1, 4, 16]

umap_df = compute_sae_umap_data(

splitting_saes, autointerp_dfs, [768 * ex for ex in expansion_factors], gpt2

)

display(umap_df.head())

Click to see the expected output

Solution

Here's the version without the HDBSCAN clustering:

def compute_sae_umap_data(

saes: dict[int, SAE],

autointerp_dfs: dict[int, pd.DataFrame],

sae_widths: list[int],

model: HookedSAETransformer,

n_neighbors_visual: int = 15,

min_dist_visual: float = 0.05,

find_clusters: bool = False,

n_neighbors_cluster: float = 15,

min_dist_cluster: float = 0.1,

min_cluster_size: int = 3,

batch_size: int = 1000,

) -> pd.DataFrame:

"""

This function will return a dataframe containing umap coordinates & other data (you can then use

this to create a plot using the code immediately below). The UMAP calculation is done over

multiple SAEs simultaneously, for comparison.

Expected dataframe columns:

sae_width: int

The width of the SAE that this feature belongs to

feature_idx: int

The index of the feature

umap_x: float

The x-coordinate of the feature in the UMAP embedding

umap_y: float

The y-coordinate of the feature in the UMAP embedding

autointerp: str

The autointerp description of this feature

top_token_strs_formatted: str

The top 10 tokens that the feature is activated by

Args:

saes: dict[int, SAE]

List of SAEs to use for the UMAP calculation

autointerp_dfs: dict[int, pd.DataFrame]

Dataframes containing autointerp descriptions for each SAE

sae_widths: list[int]

The widths of SAEs we'll be using for the UMAP calculation

model: HookedSAETransformer

The model which all the SAEs should be attached to

n_neighbors_visual: int

The number of neighbors to consider for the UMAP embedding for the visual plot

min_dist_visual: float

The minimum distance between points in the UMAP embedding for the visual plot

n_neighbors_cluster: int

The number of neighbors to consider for the UMAP embedding for the cluster plot

min_dist_cluster: float

The minimum distance between points in the UMAP embedding for the cluster plot

min_cluster_size: int

The minimum number of points in a cluster.

batch_size: int

Number of features to process at once, for logits

"""

assert not find_clusters, "Not implemented yet"

# Get initial dataframe by concatenating across SAEs (and autointerp descriptions)

sae_dfs = []

for width in sae_widths:

df = autointerp_dfs[width].copy()

df["sae_width"] = width

df["feature_idx"] = list(range(width))

sae_dfs.append(df)

feature_df = pd.concat(sae_dfs)

# Get concatenated decoder matrix

W_dec = t.cat([saes[width].W_dec for width in sae_widths])

# Get all the top boosted tokens for each feature, processing in batches

top_token_ids = []

print("Computing top logits")

for start_idx in range(0, len(feature_df), batch_size):

end_idx = min(start_idx + batch_size, len(feature_df))

batch_result = W_dec[start_idx:end_idx] @ model.W_U

top_token_ids.append(batch_result.topk(10).indices)

# Combine results from all batches, and get them into the dataframe

token_factors_inds = t.cat(top_token_ids)

feature_df["tok_token_ids"] = token_factors_inds.tolist()

feature_df["top_token_strs"] = [

", ".join(map(repr, model.to_str_tokens(tokens)))

for tokens in token_factors_inds

]

print("Calculating 2D UMAP")

visual_umap = UMAP(

n_components=2,

n_neighbors=n_neighbors_visual,

min_dist=min_dist_visual,

metric="cosine",

)

visual_umap_embedding = visual_umap.fit_transform(W_dec.cpu())

feature_df[["umap_x", "umap_y"]] = visual_umap_embedding[:, :2]

return feature_df

Use the code below to plot the data.

# For the color scale

custom_grey_green_color_scale = lambda n: ["rgba(170,170,170,0.5)"] + px.colors.n_colors(

"rgb(0,120,0)", "rgb(144,238,144)", n - 1, colortype="rgb"

)

# Make sure the points for wider SAEs are on top

umap_df = umap_df.sort_values("sae_width", ascending=False)

# Get marker size (larger for narrower SAEs)

umap_df["marker_size"] = 4 * umap_df["sae_width"] / umap_df["sae_width"].max()

px.scatter(

umap_df,

x="umap_x",

y="umap_y",

color=umap_df["sae_width"].astype(str), # for discrete colors

size="marker_size",

height=900,

width=1200,

hover_data=["description", "top_token_strs"],

labels={"umap_x": "UMAP 1", "umap_y": "UMAP 2", "color": "SAE Width"},

color_discrete_sequence=custom_grey_green_color_scale(len(expansion_factors)),

template="simple_white",

title="Feature Splitting in SAEs",

).update_traces(marker=dict(line=dict(width=0))).show()

Click to see the expected output

Exercise - add clustering

We can also perform a clustering algorithm on our embeddings, to further explore the geometric structure. Note that this exercise is more about exploring a single SAE's geometric structure, rather than the relationship between different SAEs.

HDBSCAN is a hierarchical clustering algorithm which transforms the space according to its density, and then constructs clusters based on a minimum spanning tree of this transformed space. You can read about it in more detail here. The standard way to apply a clustering algorithm like this is:

- Create a high-dimensional Umap (at least higher than 2 dimensions, e.g. a number like 10)

- Fit a clusterer using the following code:

clusterer = hdbscan.HDBSCAN(min_cluster_size=min_cluster_size)

clusterer.fit(clustering_umap_embedding)

- Extract the labels via

clusterer.labels_, and get them into the dataframe

You can edit your previous function, by including this logic if find_clusters is True.

# This took about 50s to run for me in Colab Pro+, 90s on my VastAI A100 remote machine

umap_df = compute_sae_umap_data(

splitting_saes, autointerp_dfs, [widths[5]], gpt2, find_clusters=True

)

display(umap_df.head())

px.scatter(

umap_df,

x="umap_x",

y="umap_y",

color="cluster",

height=900,

width=1200,

hover_data=["description", "top_token_strs"],

labels={"umap_x": "UMAP 1", "umap_y": "UMAP 2"},

template="simple_white",

title=f"2D UMAP for SAE width = {widths[5]}, clustering algorithm = HDBSCAN from 10D UMAP embedding",

).update_traces(marker=dict(size=4, line=dict(width=0))).update_layout(showlegend=False)

Click to see the expected output

Solution

Here's the code to insert at the end of your function, if find_clusters is True:

print("Calculating 10D UMAP")

clustering_umap = UMAP(

n_components=10,

n_neighbors=n_neighbors_cluster,

min_dist=min_dist_cluster,

metric="cosine",

)

clustering_umap_embedding = clustering_umap.fit_transform(W_dec.cpu())

clusterer = hdbscan.HDBSCAN(min_cluster_size=min_cluster_size)

clusterer.fit(clustering_umap_embedding)

feature_df["cluster"] = clusterer.labels_

feature_df.sort_values("cluster", inplace=True)

feature_df["cluster"] = feature_df["cluster"].astype(str)

Feature Absorption

Note - this section is not complete. Exercises will be added over the next ~month, based on replicating the results from the feature absorption paper.

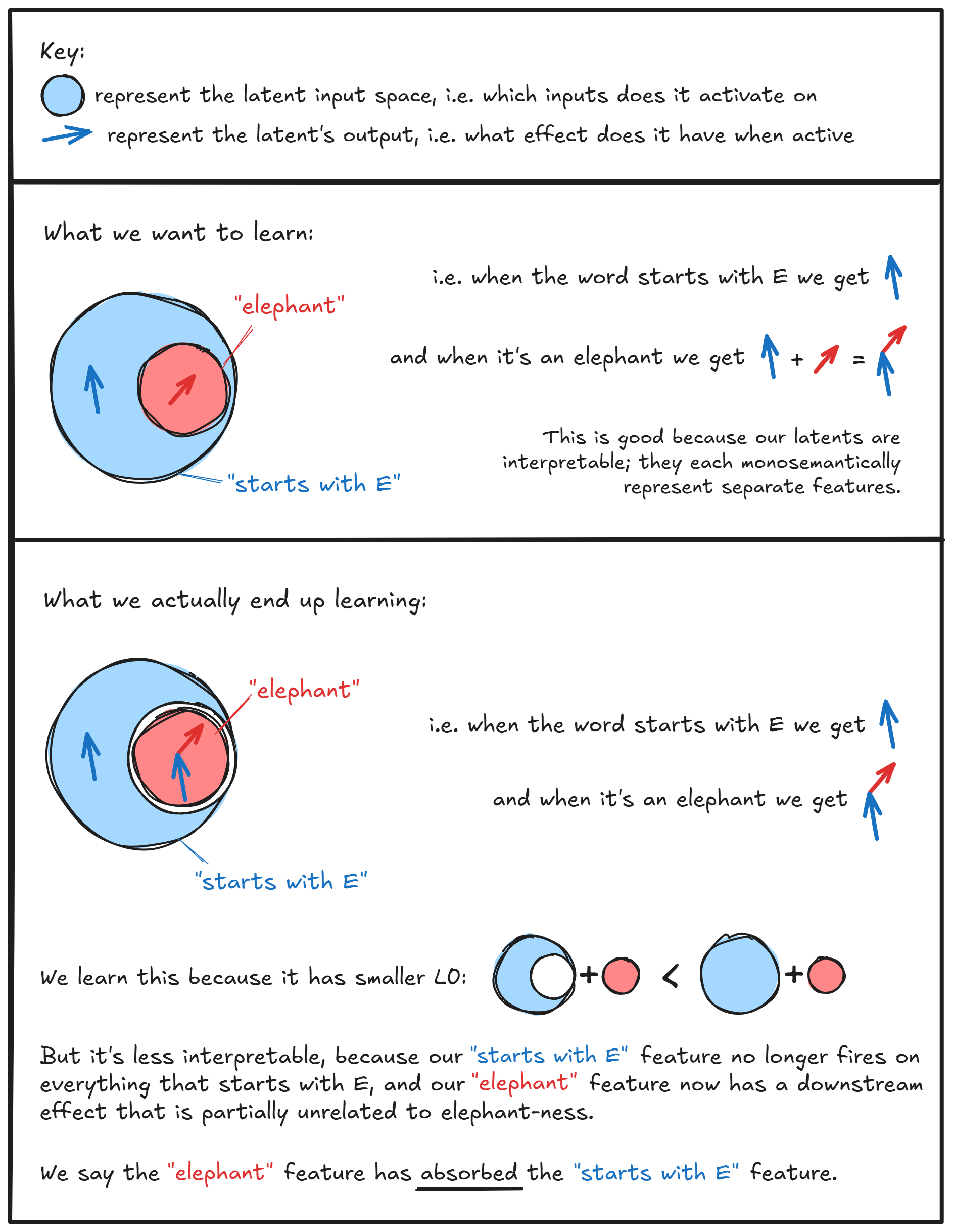

Feature absorption is a very interesting topic, and the most recent work to be published about at the time I'm writing this material (the post on it came out this week). To quote from the paper, the phenomenon of feature absorption is as follows:

- An SAE latent appears to track a human-interpretable concept (such as "starts with E").

- That SAE latent fails to activate on seemingly arbitrary examples (eg "Elephant").

- We find "absorbing" latents which weakly project onto the feature direction and causally mediate in-place of the main latent (eg: an "elephants" latent absorbs the "starts with E" feature direction, and then the SAE no longer fires the "starts with E" latent on the token "Elephant", as the "elephants" latent now encodes that information, along with other semantic elephant-related features).

Note that feature absorption also complicates the picture of feature splitting we gave above. In the view of feature splitting, a single latent in a narrow SAE can split into multiple more specific latents in a wider SAE. In this picture, our ability to predict SAE activations is still good, and we should expect to find sparse circuits in our model. But feature absorption is a problem which still persists even at large SAE widths, and it might impair not only our ability to predict SAE activations, but also to find sparse circuits (because our SAE no longer gives is a decomposition with a sparse set of causal mediators). Furthermore, feature absorption seems like a problem which stems directly from the sparsity penalty (since it allows the "starts with E" feature to fire less, without making the "Elephant" feature fire more), making it very hard to fix.

Here's a diagram which illustrates feature absorption:

The work done in this paper primarily identifies and characterizes the problem of feature absorption. A generalized solution to this problem hasn't yet been proposed, making it a particularly exciting area of study! However, one part of the answer might be...

Meta-SAEs

Note - this section is not complete. Exercises will be added over the next ~month, based on replicating the results from the Meta-SAEs paper.

Meta SAEs are a special type of SAE, trained to reconstruct the decoder directions of a normal SAE. This allows us to find sparse reconstructions of the base SAE latents, in situations where the SAE latents aren't monosemantic (see the prior section on feature absorption for an explanation of why we might not always expect SAE latents to be monosemantic). The paper on Meta-SAEs finds the following key results:

- SAE latents can be decomposed into more atomic, interpretable meta-latents.

- We show that when latents in a larger SAE have split out from latents in a smaller SAE, a meta SAE trained on the larger SAE often recovers this structure.

- We demonstrate that meta-latents allow for more precise causal interventions on model behavior than SAE latents on a targeted knowledge editing task.

You can visit the dashboard which the authors built, that lets you explore meta-SAE latents.

Logit Lens

Note - this section is not complete. Exercises will be added over the next ~month, based on replicating the results from the LessWrong post Understanding SAE Features with the Logit Lens, and will cover the topics of universal features & token enrichment analysis.

Autointerp

Note - we strongly recommend completing the material on automated interpretability in 1️⃣ Intro to SAE Interpretability, before moving on to this section.

In this section, we'll take a deeper dive into automated interpretability. In particular, we'll cover 2 topics:

- Using automated interpretability to score our feature explanations (using this as a method for evaluating SAEs),

- Using patch scoping as a potental high computational speedup to the generation phase of autointerp.

Scoring autointerp explanations

To review what we covered before, when we briefly discussed autointerp & SAE evals:

SAE evaluations are the ways we measure "how good our SAE is" in a varity of different ways. It turns out this is very hard, because any metric we pick is vulnerable to Goodhearting and not necessarily representative of what we want out of our SAEs. For example, it seems like sparser latents are often more interpretable (if reconstruction loss is held constant), which is why a common way to evaluate SAEs is along a Pareto frontier of latent sparsity & reconstruction loss. But what if sparsity doesn't lead to more interpretable latents (e.g. because of feature absorption)? Autointerp provides an alternative way of evaluating SAE interpretability, because we can directly quantify how good our latent explanations are! The idea is to convert latent explanations into a set of predictions on some test set of prompts, and then score the accuracy of those predictions. More interpretable latents should lead to better predictions, because the latents will tend to have monosemantic and human-interpretable patterns that can be predicted from their given explanations.

When scoring, we want to balance between recall (identifying text where the latent activates) and precision (avoiding false positives). For example, suppose we have a latent that fires on the word "stop", in phrases like "don't stop" or "won't stop". We might have the following 2 types of incorrect types of explanation:

| Description | Recall | Precision | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 'The latent activates on the word "stop"' | High | Low | This identifies all positive examples, but also has many false positives. |

| 'The latent activates on the word "stop" in the phrase "don't stop"' | Low | High | This only identifies half the positive examples, but has no false positives. |

These can be pretty difficult problems to solve. For example, in order to fix the problem of low precision, we'd need to exhibit example sequences containing the word "stop" in contexts other than "don't stop" or "won't stop", showing the model that the activations here are zero. Unfortunately, it's not obvious how to generate these false positive examples, because the sequences we're using in our autointerp are usually either sampled from the latent's top activating sequences (meaning they'll only contain "stop" inside phrases "don't stop" or "won't stop") or drawn randomly from the full dataset (in which case we shouldn't expect them to contain the word "stop" with particularly high frequency). These problems may well become worse as we scale to larger SAEs and sparser, more specific latents.

If you've not already loaded in the following model & SAE from earlier sections, then run the code block below to do so:

gpt2 = HookedSAETransformer.from_pretrained("gpt2-small", device=device)

gpt2_sae = SAE.from_pretrained(

release="gpt2-small-res-jb",

sae_id="blocks.7.hook_resid_pre",

device=str(device),

)[0]

gpt2_act_store = ActivationsStore.from_sae(

model=gpt2,

sae=gpt2_sae,

streaming=True,

store_batch_size_prompts=16,

n_batches_in_buffer=32,

device=str(device),

)

Exercise - implement autointerp scoring

There are several different methods of scoring that have been explored in the literature. For example, we have simulation scoring (from the original OpenAI "Language models can explain neurons in language models" paper) which assigns an activation to each token in a text, then measures the correlation between predicted and real activations. However, we'll be using a slightly easier-to-implement method: detection, i.e. giving the model a random sample of sequences (some of which are drawn from its top activating sequences, and others randomly from our dataset) and asking it to classify whether each sequence contains the latent in question. We can then measure the accuracy of its predictions - for example, if we pick 5 random sequences and 3 top activating sequences (ordered so that #1, #3, #7 are the top activating sequences), and our model predicted #1, #3, #6, then we'd have a score of 6/8 = 75% (since all sequences were correctly classified except for #6 and #7).

We've set up some infrastructure for you below, to help you get started with autointerp scoring. Firstly, we have the Example class, which will help you more easily organize the return data you get from performing forward passes. Note that this class is initialized with act_threshold, which is the activation value over which we'll consider a token to be "active". This is important because often it won't just be the max-activation token which is active in a given sequence.

class Example:

"""

Data for a single example sequence.

"""

def __init__(

self, toks: list[int], acts: list[float], act_threshold: float, model: HookedSAETransformer

):

self.toks = toks

self.str_toks = model.to_str_tokens(t.tensor(self.toks))

self.acts = acts

self.act_threshold = act_threshold

self.toks_are_active = [act > act_threshold for act in self.acts]

self.is_active = any(self.toks_are_active) # this is what we predict in the scoring phase

def to_str(self, mark_toks: bool = False) -> str:

return (

"".join(

f"<<{tok}>>" if (mark_toks and is_active) else tok

for tok, is_active in zip(self.str_toks, self.toks_are_active)

)

.replace(">><<", "")

.replace("�", "")

.replace("\n", "↵")

)

ex = Example(

toks=[1212, 1276, 307, 3635, 13, 314, 1239, 714, 651, 262, 8181, 286, 48971, 12545, 13],

acts=[0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0],

act_threshold=0.5,

model=gpt2,

)

print(ex.str_toks)

print(ex.to_str(mark_toks=True))

['This', ' must', ' be', ' Thursday', '.', ' I', ' never', ' could', ' get', ' the', ' hang', ' of', ' Thurs', 'days', '.'] This must be<< Thursday>>. I never could get the hang of<< Thursdays>>.

Next, we've given you an AutoInterpConfig class which holds all the parameters you'll need to set for autointerp generation & scoring. You should look through the docstring here, and make sure you understand what each parameter does. A few things to call attention to:

- In this implementation of autointerp, you can parallelize it over multiple latents at once, rather than just one at a time.

- The data collection process will involve collecting

n_top_ex_for_generation + n_top_ex_for_scoringtop activations from the input data (we've given you then_top_exproperty for this), as well asn_random_ex_for_scoringrandom sequences. The generation phase involves using a randomly chosenn_top_ex_for_generationtop examples and producing an explanation from them, and the scoring phase involves shuffling together then_top_ex_for_scoringtop examples and then_random_ex_for_scoringrandom examples, and asking the model to classify which is which.

@dataclass

class AutoInterpConfig:

"""

Controls all parameters for how autointerp will work.

Arguments:

latents: The latent indices we'll be studying

buffer: The size of the buffer to use for scoring

no_overlap: Whether to allow overlapping sequences for scoring

act_threshold_frac: The fraction of the maximum act to use as the act threshold

total_tokens: The total number of tokens we'll gather data for.

scoring: Whether to perform the scoring phase, or just return explanation

max_tokens_in_explanation: The maximum number of tokens to allow in an explanation

n_top_ex_for_generation: The number of top activating sequences to use for generation

n_top_ex_for_scoring: The number of top sequences to use for scoring

n_random_ex_for_scoring: The number of random sequences to use for scoring

"""

latents: list[int]

buffer: int = 10

no_overlap: bool = False

act_threshold_frac: float = 0.1

total_tokens: int = 500_000

scoring: bool = False

max_tokens_in_explanation: int = 25

use_examples_in_explanation_prompt: bool = True

n_top_ex_for_generation: int = 10

n_top_ex_for_scoring: int = 4

n_random_ex_for_scoring: int = 8

@property

def n_top_ex(self):

"""When fetching data, we get the top examples for generation & scoring simultaneously."""

return self.n_top_ex_for_generation + self.n_top_ex_for_scoring

@property

def max_tokens_in_prediction(self) -> int:

"""Predictions take the form of comma-separated numbers, which should all be single toks."""

return 2 * self.n_ex_for_scoring + 5

@property

def n_ex_for_scoring(self) -> int:

"""For scoring phase, we use a randomly shuffled mix of top-k activations and random seqs."""

return self.n_top_ex_for_scoring + self.n_random_ex_for_scoring

@property

def n_latents(self) -> int:

return len(self.latents)

Finally, we have the AutoInterp class. This is initialized with a config, and it contains the following important methods:

gather_data, which collects the data we'll use for the generation phase. It does this by computing the top k for every batch it goes through, concatenating them together into a single tensor of lengthn_top_ex_for_generation * n_batches, then getting the topn_top_ex_for_generationfrom this.get_generation_prompts, which uses the data fromgather_datato return prompts for the generation phase.get_response, which performs a generic API call to OpenAI and returns the responses.run, which runs the full autointerp pipeline (currently only generation is implemented).

You should first run the code block below, and make sure you understand how the generation phase work. When you do, then you can try and implement the scoring phase. This will require filling out or adding to the following methods:

get_scoring_prompts

This should return the prompts that will be used in the scoring phase. You can follow a similar structure to the get_generation_prompts method, but obviously asking for predictions on certain examples rather than explanations.

A few bits of guidance:

- Make sure not to use

mark_toks=Truein theto_strmethod of your examples, because you obviously don't want to tell the model which sequences are active! - You should tell the model exactly what format to return its predictions in, so that you can easily parse them. For example, you could ask for comma-separated lists of numbers like

1, 4, 7(and also specify that it should sayNoneif it thinks there are no activating sequences). - You might also want to write a

parse_predictionsmethod, for taking the model's response and parsing it back into a list of integers.

Recommended structure for the scoring phase prompts (although we recommend trying your own before reading this one!)

You should be able to get by with just a system & user prompt, no assistant prompt.

{

"system": f"""We're studying neurons in a neural network. Each neuron activates on some particular word or concept in a short document. You will be given a short explanation of what this neuron activates for, and then be shown {n_ex_for_scoring} example sequences. You will have to return the examples where you think the neuron should activate at least once, in the form of a comma-separated list. For example, your response might look like "1, 4, 7". If you think there are no examples where the neuron should activate, you should just respond with "None". You should include nothing else in your response other than comma-separated numbers or the word "None" - this is important.""",

"user": f"Here is the explanation: this neuron fires on {explanation}.\n\nHere are the examples:\n\n{examples_as_str}",

}

gather_data

You'll need to rewrite this method to collect the data you need for the scoring phase. Rather than just returning n_top_ex_for_generation examples for the generation phase, it also returns n_top_ex_for_scoring top examples for the scoring phase (which are shuffled together with n_random_ex_for_scoring random examples). We recommend these random examples be chosen from across all batches in the dataset that you iterate through in this function, and that they should be different for each latent. (Note - in practice you might want to also return the activations for the randomly chosen example sequences to check whether these should be classified as activating, however if your SAE is sufficiently sparse then most randomly chosen sequences have a very low probability of activating, so for the purposes of this exercise it's fine to assume that randomly chosen sequences won't activate.)

run

You'll need to add code to the run method, to (1) get scoring prompts from the n_top_ex_for_scoring top examples & n_random_ex_for_scoring random sequences, (2) return & parse predictions from those prompts, and (3) score the predictions (where the score is defined as fraction of correct classifications out of the total n_top_ex_for_scoring + n_random_ex_for_scoring).

Some final tips:

- We've given you a

debugflag in therunmethod. If this is set toTrue, then in the generation & scoring phases we'll print out useful information about what the prompt & raw responses were. You should make use of this to debug your code, if you're at the point where it's running successfully but getting low scores (basically anything less than 75% for the scoring phase on latents which seem clearly interpretable is pretty bad). - You can also use the

display_dashboardfunction to sanity check the latents you're choosing, to make sure that they're interpretable and should be getting good scores. - If you want to speed up debugging feedback loops, you can run the

self.gather_data()method manually, and rewriterunso that it can optionally take the output of this method as an argument - that way when you edit the run function & call it again, you can jump straight to the API querying section rather than waiting for the data collection to run again. - Make sure to avoid off-by-one indexing errors, e.g. where you label your examples from 0 to n-1 but store your classifications from 1 to n. (I'm totally not saying that because I spent half an hour debugging this function before realizing I was doing this, absolutely not.)

Messages: TypeAlias = list[dict[Literal["role", "content"], str]]

def display_messages(messages: Messages):

print(

tabulate([m.values() for m in messages], tablefmt="simple_grid", maxcolwidths=[None, 120])

)

class AutoInterp:

"""

This is a start-to-end class for generating explanations and optionally scores. It's easiest to

implement it as a single class for the time being because there's data we'll need to fetch

that'll be used in both the generation and scoring phases.

"""

def __init__(

self,

cfg: AutoInterpConfig,

model: HookedSAETransformer,

sae: SAE,

act_store: ActivationsStore,

api_key: str,

):

self.cfg = cfg

self.model = model

self.sae = sae

self.act_store = act_store

self.api_key = api_key

def run(self, debug: bool = False) -> dict[int, dict[str, Any]]:

"""Runs both generation & scoring phases, and returns the results in a dictionary."""

generation_examples, scoring_examples = self.gather_data()

results = {}

for latent in tqdm(self.cfg.latents, desc="Querying OpenAI api"):

gen_prompts = self.get_generation_prompts(generation_examples[latent])

explanation_raw = self.get_response(

gen_prompts,

max_tokens=self.cfg.max_tokens_in_explanation,

debug=debug and (latent == self.cfg.latents[0]),

)[0]

explanation = self.parse_explanation(explanation_raw)

results[latent] = {"explanation": explanation}

if self.cfg.scoring:

raise NotImplementedError()

return results

def parse_explanation(self, explanation: str) -> str:

return explanation.split("activates on")[-1].rstrip(".").strip()

def get_response(

self, messages: list[dict], max_tokens: int, n_completions: int = 1, debug: bool = False

) -> str:

"""Generic API usage function for OpenAI"""

for message in messages:

assert message.keys() == {"content", "role"}

assert message["role"] in ["system", "user", "assistant"]

client = OpenAI(api_key=self.api_key)

result = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-4o-mini",

messages=messages,

n=n_completions,

max_tokens=max_tokens,

stream=False,

)

if debug:

display_messages(

messages + [{"role": "assistant", "content": result.choices[0].message.content}]

)

return [choice.message.content.strip() for choice in result.choices]

def get_generation_prompts(self, generation_examples: list[Example]) -> Messages:

assert len(generation_examples) > 0, "No generation examples found"

examples_as_str = "\n".join(

[f"{i + 1}. {ex.to_str(mark_toks=True)}" for i, ex in enumerate(generation_examples)]

)

SYSTEM_PROMPT = """We're studying neurons in a neural network. Each neuron activates on some particular word/words or concept in a short document. The activating words in each document are indicated with << ... >>. Look at the parts of the document the neuron activates for and summarize in a single sentence what the neuron is activating on. Try to be specific in your explanations, although don't be so specific that you exclude some of the examples from matching your explanation. Pay attention to things like the capitalization and punctuation of the activating words or concepts, if that seems relevant. Keep the explanation as short and simple as possible, limited to 20 words or less. Omit punctuation and formatting. You should avoid giving long lists of words."""

if self.cfg.use_examples_in_explanation_prompt:

SYSTEM_PROMPT += """ Some examples: "This neuron activates on the word 'knows' in rhetorical questions like 'Who knows ... ?'", and "This neuron activates on verbs related to decision-making and preferences", and "This neuron activates on the substring 'Ent' at the start of words like 'Entrepreneur' or 'Entire'."""

else:

SYSTEM_PROMPT += (

"""Your response should be in the form "This neuron activates on..."."""

)

USER_PROMPT = f"""The activating documents are given below:\n\n{examples_as_str}"""

return [

{"role": "system", "content": SYSTEM_PROMPT},

{"role": "user", "content": USER_PROMPT},

]

def get_scoring_prompts(self, explanation: str, scoring_examples: list[Example]) -> Messages:

assert len(scoring_examples) > 0, "No scoring examples found"

raise NotImplementedError()

def gather_data(self) -> tuple[dict[int, list[Example]], dict[int, list[Example]]]:

"""

Stores top acts / random seqs data, which is used for generation & scoring respectively.

"""

sae_acts_post_hook_name = f"{self.sae.cfg.hook_name}.hook_sae_acts_post"

total_batches = self.cfg.total_tokens // (self.act_store.store_batch_size * self.act_store.context_size)

# Dictionary to store data for each latent

latent_data = {

latent: {

"top_toks": t.empty(0, 1 + 2 * self.cfg.buffer, dtype=t.int64, device=device),

"top_values": t.empty(0, dtype=t.float32, device=device),

}

for latent in self.cfg.latents

}

for batch in tqdm(range(total_batches), desc="Collecting activations data"):

_, cache = self.model.run_with_cache_with_saes(

tokens := self.act_store.get_batch_tokens().to(device),

saes=[self.sae],

stop_at_layer=self.sae.cfg.hook_layer + 1,

names_filter=[sae_acts_post_hook_name],

)

acts = cache[sae_acts_post_hook_name][..., self.cfg.latents]

del cache

for i, latent in enumerate(self.cfg.latents):

# Get top activations from this batch, and filter down to the data we'll actually include

top_indices = get_k_largest_indices(

acts[..., i],

k=self.cfg.n_top_ex_for_generation,

buffer=self.cfg.buffer,

no_overlap=self.cfg.no_overlap,

)

top_toks = index_with_buffer(tokens, top_indices, buffer=self.cfg.buffer)

top_values = index_with_buffer(acts[..., i], top_indices, buffer=self.cfg.buffer)

latent_data[latent]["top_toks"] = t.cat(

(latent_data[latent]["top_toks"], top_toks), dim=0

)

latent_data[latent]["top_values"] = t.cat(

(latent_data[latent]["top_values"], top_values), dim=0

)

# Dicts to store all generation & scoring examples for each latent

generation_examples = {}

scoring_examples = {}

for i, latent in enumerate(self.cfg.latents):

top_toks = latent_data[latent]["top_toks"]

top_values = latent_data[latent]["top_values"]

topk = top_values[:, self.cfg.buffer].topk(self.cfg.n_top_ex_for_generation).indices

act_threshold = self.cfg.act_threshold_frac * latent_data[latent]["max_act"]

generation_examples[latent] = [

Example(

toks=top_toks[topk[j]].tolist(),

acts=top_values[topk[j]].tolist(),

act_threshold=act_threshold,

model=self.model,

)

for j in range(len(topk))

]

return generation_examples, scoring_examples

Solution

Messages: TypeAlias = list[dict[Literal["role", "content"], str]]

def display_messages(messages: Messages):

print(

tabulate([m.values() for m in messages], tablefmt="simple_grid", maxcolwidths=[None, 120])

)

class AutoInterp:

"""

This is a start-to-end class for generating explanations and optionally scores. It's easiest to

implement it as a single class for the time being because there's data we'll need to fetch

that'll be used in both the generation and scoring phases.

"""

def __init__(

self,

cfg: AutoInterpConfig,

model: HookedSAETransformer,

sae: SAE,

act_store: ActivationsStore,

api_key: str,

):

self.cfg = cfg

self.model = model

self.sae = sae

self.act_store = act_store

self.api_key = api_key

def run(self, debug: bool = False) -> dict[int, dict[str, Any]]:

"""Runs both generation & scoring phases, and returns the results in a dictionary."""

generation_examples, scoring_examples = self.gather_data()

results = {}

for latent in tqdm(self.cfg.latents, desc="Querying OpenAI api"):

gen_prompts = self.get_generation_prompts(generation_examples[latent])

explanation_raw = self.get_response(

gen_prompts,

max_tokens=self.cfg.max_tokens_in_explanation,

debug=debug and (latent == self.cfg.latents[0]),

)[0]

explanation = self.parse_explanation(explanation_raw)

results[latent] = {"explanation": explanation}

if self.cfg.scoring:

scoring_prompts = self.get_scoring_prompts(explanation, scoring_examples[latent])

predictions = self.get_response(

scoring_prompts,

max_tokens=self.cfg.max_tokens_in_prediction,

debug=debug and (latent == self.cfg.latents[0]),

)[0]

predictions_parsed = self.parse_predictions(predictions)

score = self.score_predictions(predictions_parsed, scoring_examples[latent])

results[latent] |= {

"predictions": predictions_parsed,

"correct seqs": [

i for i, ex in enumerate(scoring_examples[latent], start=1) if ex.is_active

],

"score": score,

}

return results

def parse_explanation(self, explanation: str) -> str:

return explanation.split("activates on")[-1].rstrip(".").strip()

def parse_predictions(self, predictions: str) -> list[int]:

predictions_split = predictions.strip().rstrip(".").replace("and", ",").split(",")

predictions_list = [i.strip() for i in predictions_split if i.strip() != ""]

if predictions_list == ["None"]:

return []

assert all(pred.strip().isdigit() for pred in predictions_list), (

f"Prediction parsing error: predictions should be comma-separated numbers, found {predictions!r}"

)

predictions = [int(pred.strip()) for pred in predictions_list]

return predictions

def score_predictions(self, predictions: list[str], scoring_examples: list[Example]) -> float:

classifications = [i in predictions for i in range(1, len(scoring_examples) + 1)]

correct_classifications = [ex.is_active for ex in scoring_examples]

return sum([c == cc for c, cc in zip(classifications, correct_classifications)]) / len(

classifications

)

def get_response(

self, messages: list[dict], max_tokens: int, n_completions: int = 1, debug: bool = False

) -> str:

"""Generic API usage function for OpenAI"""

for message in messages:

assert message.keys() == {"content", "role"}

assert message["role"] in ["system", "user", "assistant"]

client = OpenAI(api_key=self.api_key)

result = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-4o-mini",

messages=messages,

n=n_completions,

max_tokens=max_tokens,

stream=False,

)

if debug:

display_messages(

messages + [{"role": "assistant", "content": result.choices[0].message.content}]

)

return [choice.message.content.strip() for choice in result.choices]

def get_generation_prompts(self, generation_examples: list[Example]) -> Messages:

assert len(generation_examples) > 0, "No generation examples found"

examples_as_str = "\n".join(

[f"{i + 1}. {ex.to_str(mark_toks=True)}" for i, ex in enumerate(generation_examples)]

)

SYSTEM_PROMPT = """We're studying neurons in a neural network. Each neuron activates on some particular word/words or concept in a short document. The activating words in each document are indicated with << ... >>. Look at the parts of the document the neuron activates for and summarize in a single sentence what the neuron is activating on. Try to be specific in your explanations, although don't be so specific that you exclude some of the examples from matching your explanation. Pay attention to things like the capitalization and punctuation of the activating words or concepts, if that seems relevant. Keep the explanation as short and simple as possible, limited to 20 words or less. Omit punctuation and formatting. You should avoid giving long lists of words."""

if self.cfg.use_examples_in_explanation_prompt:

SYSTEM_PROMPT += """ Some examples: "This neuron activates on the word 'knows' in rhetorical questions like 'Who knows ... ?'", and "This neuron activates on verbs related to decision-making and preferences", and "This neuron activates on the substring 'Ent' at the start of words like 'Entrepreneur' or 'Entire'."""

else:

SYSTEM_PROMPT += (

"""Your response should be in the form "This neuron activates on..."."""

)

USER_PROMPT = f"""The activating documents are given below:\n\n{examples_as_str}"""

return [

{"role": "system", "content": SYSTEM_PROMPT},

{"role": "user", "content": USER_PROMPT},

]

def get_scoring_prompts(self, explanation: str, scoring_examples: list[Example]) -> Messages:

assert len(scoring_examples) > 0, "No scoring examples found"

examples_as_str = "\n".join(

[f"{i + 1}. {ex.to_str(mark_toks=False)}" for i, ex in enumerate(scoring_examples)]

)

SYSTEM_PROMPT = f"""We're studying neurons in a neural network. Each neuron activates on some particular word/words or concept in a short document. You will be given a short explanation of what this neuron activates for, and then be shown {self.cfg.n_ex_for_scoring} example sequences. You will have to return a comma-separated list of the examples where you think the neuron should activate at least once. For example, your response might look like "1, 4, 7, 8". If you think there are no examples where the neuron will activate, you should just respond with "None". You should include nothing else in your response other than comma-separated numbers or the word "None" - this is important."""

USER_PROMPT = f"Here is the explanation: this neuron fires on {explanation}.\n\nHere are the examples:\n\n{examples_as_str}"

return [

{"role": "system", "content": SYSTEM_PROMPT},

{"role": "user", "content": USER_PROMPT},

]

def gather_data(self) -> tuple[dict[int, list[Example]], dict[int, list[Example]]]:

"""

Stores top acts / random seqs data, which is used for generation & scoring respectively.

"""

sae_acts_post_hook_name = f"{self.sae.cfg.hook_name}.hook_sae_acts_post"

batch_size, seq_len = self.act_store.store_batch_size_prompts, self.act_store.context_size

total_seqs = self.cfg.total_tokens // seq_len

total_batches = total_seqs // batch_size

# Get indices we'll take our random examples from, over all batches (and over all latents)

all_rand_indices_shape = (self.cfg.n_random_ex_for_scoring, self.cfg.n_latents)

all_rand_indices = t.stack(

[

t.randint(0, total_batches, all_rand_indices_shape), # which batch

t.randint(0, batch_size, all_rand_indices_shape), # which sequence in the batch

t.randint(

self.cfg.buffer, seq_len - self.cfg.buffer, all_rand_indices_shape

), # where in the sequence

],

dim=-1,

) # shape [n_random_ex_for_scoring, n_latents, 3]

# Dictionary to store data for each latent

latent_data = {

latent: {

"rand_toks": t.empty(0, 1 + 2 self.cfg.buffer, dtype=t.int64, device=device),

"top_toks": t.empty(0, 1 + 2 self.cfg.buffer, dtype=t.int64, device=device),

"top_values": t.empty(0, dtype=t.float32, device=device),

}

for latent in self.cfg.latents

}

for batch in tqdm(range(total_batches), desc="Collecting activations data"):

_, cache = self.model.run_with_cache_with_saes(

tokens := self.act_store.get_batch_tokens().to(device),

saes=[self.sae],

stop_at_layer=self.sae.cfg.hook_layer + 1,

names_filter=[sae_acts_post_hook_name],

)

acts = cache[sae_acts_post_hook_name][..., self.cfg.latents]

del cache

for i, latent in enumerate(self.cfg.latents):

# Get top activations from this batch, and filter down to the data we'll actually include

top_indices = get_k_largest_indices(

acts[..., i],

k=self.cfg.n_top_ex,

buffer=self.cfg.buffer,

no_overlap=self.cfg.no_overlap,

)

top_toks = index_with_buffer(tokens, top_indices, buffer=self.cfg.buffer)

top_values = index_with_buffer(acts[..., i], top_indices, buffer=self.cfg.buffer)

latent_data[latent]["top_toks"] = t.cat(

(latent_data[latent]["top_toks"], top_toks), dim=0

)

latent_data[latent]["top_values"] = t.cat(

(latent_data[latent]["top_values"], top_values), dim=0

)

# Get random activations (our all_rand_indices tensor tells us which random sequences to take)

rand_indices = all_rand_indices[all_rand_indices[:, i, 0] == batch, i, 1:]

random_toks = index_with_buffer(tokens, rand_indices, self.cfg.buffer)

latent_data[latent]["rand_toks"] = t.cat(

(latent_data[latent]["rand_toks"], random_toks), dim=0

)

# Dicts to store all generation & scoring examples for each latent

generation_examples = {}

scoring_examples = {}

for i, latent in enumerate(self.cfg.latents):

top_toks = latent_data[latent]["top_toks"]

top_values = latent_data[latent]["top_values"]

# From our tensor of n_top_examples n_batches top examples, get only the top

# n_top_examples of them

topk = top_values[:, self.cfg.buffer].topk(self.cfg.n_top_ex).indices

act_threshold = self.cfg.act_threshold_frac top_values.max().item()

rand_split_indices = t.randperm(self.cfg.n_top_ex)

# generation_examples[latent] = random sample of some of the top activating sequences

generation_examples[latent] = [

Example(

toks=top_toks[topk[j]].tolist(),

acts=top_values[topk[j]].tolist(),

act_threshold=act_threshold,

model=self.model,

)

for j in sorted(rand_split_indices[: self.cfg.n_top_ex_for_generation])

]

# scoring_examples[latent] = random mix of the sampled top activating sequences & random

# examples (with the top activating sequences chosen to have zero overlap with those

# used in generation_examples)

scoring_examples[latent] = random.sample(

[

Example(

toks=top_toks[topk[j]].tolist(),

acts=top_values[topk[j]].tolist(),

act_threshold=act_threshold,

model=self.model,

)

for j in rand_split_indices[self.cfg.n_top_ex_for_generation :]

]

+ [

Example(

toks=random_toks.tolist(),

acts=[0.0 for _ in random_toks],

act_threshold=act_threshold,

model=self.model,

)

for random_toks in latent_data[latent]["rand_toks"]

],

k=self.cfg.n_ex_for_scoring,

)

return generation_examples, scoring_examples

Here's an example of running just the generation phase, which should work out of the box:

latents = [9, 11, 15, 16873]

API_KEY = os.environ.get("OPENAI_API_KEY", None)

assert API_KEY is not None, "Please set your own OpenAI key."

autointerp = AutoInterp(

cfg=AutoInterpConfig(latents=latents, scoring=False),

model=gpt2,

sae=gpt2_sae,

act_store=gpt2_act_store,

api_key=API_KEY,

)

results = autointerp.run(debug=False)

print(

tabulate(

[[latent, *results[latent].values()] for latent in latents],

headers=["Feature"] + list(results[latents[0]].keys()),

tablefmt="simple_outline",

)

)

┌──────────┬────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ Latent │ explanation │ ├──────────┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │ 9 │ the word 'new' in contexts discussing recent changes or updates to rules and policies │ │ 11 │ variations of the substring "Rel" in different contexts including discussions of relationships, relative terms, and traits │ │ 15 │ the phrases 'credit card', 'debit card', and variations of 'card' in financial contexts │ │ 16873 │ phrases indicating universal testimony and guidance, particularly in religious and moral contexts │ └──────────┴────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

And here's some code running the scoring phase, which should work once you've solved the exercise:

latents = [9, 11, 15, 16873]

autointerp = AutoInterp(

cfg=AutoInterpConfig(latents=latents, scoring=True),

model=gpt2,

sae=gpt2_sae,

act_store=gpt2_act_store,

api_key=API_KEY,

)

results = autointerp.run(debug=False)

print(

tabulate(

[[latent, *results[latent].values()] for latent in latents],

headers=["Feature"] + list(results[latents[0]].keys()),

tablefmt="simple_outline",

floatfmt=".2f",

)

)

Click to see the expected output

┌──────────┬─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┬───────────────┬────────────────┬─────────┐ │ Latent │ explanation │ predictions │ correct seqs │ score │ ├──────────┼─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┼───────────────┼────────────────┼─────────┤ │ 9 │ the word 'new' in contexts referring to recently introduced services, rules, or entities │ [1, 7, 8, 9] │ [1, 7, 8, 9] │ 1.00 │ │ 11 │ the substring 'Rel' in various contexts and capitalizations │ [2, 4, 8, 11] │ [2, 4, 8, 11] │ 1.00 │ │ 15 │ the phrases related to credit and payment cards including specific mentions of 'credit card' and 'payment card' │ [2, 3, 7, 12] │ [2, 3, 7, 12] │ 1.00 │ │ 16873 │ the phrase "all these things shall be added unto you" and related concepts about not worrying for the future │ [2, 3, 10] │ [2, 3, 9, 10] │ 0.92 │ └──────────┴─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┴───────────────┴────────────────┴─────────┘

Bonus - make improvements to autointerp

This is a very barebones implementation of autointerp, and could be improved in a number of ways. We list a few below, you're welcome to try any of these as well as other ideas you can think of!

- Use asyncio to speed up API queries. The data gathering is parallelized across latents (most of the computation time is in the forward pass, not the for loop over latents to get max activations), but the same isn't true for querying the OpenAI API - this is currently implemented in a for loop, which is pretty inefficient. The operation of querying OpenAI's API is I/O bottlenecked, meaning you should be able to make it faster using libraries like

asyncio. Can you get this working? (Note, this particular extension might not be well suited to working in a Colab or Jupyter notebook.) - Use explanations for generation. Can you set up a third pipeline (alongside generation & scoring) which takes in the explanations produced during the generation phase, and uses them to produce sequences which the model thinks is likely to cause the latent to activate (as described by EleutherAI here). Does your model produce false positives in these cases? If so, can you use those examples in your generation phase to improve your explanation precision, reducing the number of false positive classifications?

- Measure precision using latent neighbours. Again as described by EleutherAI here - can you measure the precision of your explanations by finding latents with high decoder cosine similarity to each other, and seeing whether the explanation is sufficient to distinguish between whether a sequence activates one latent or the other? To take a different perspective, can you take top activating sequences from neighbouring latents, and use them as false positives in your generation phase to help improve the precision of your explanations?

- Benchmark autointerp against neurons / random latents. Anthropic found that autointerp on SAE latents consistently outperformed autointerp on transformer neurons or randomly initialized latents (which is a good sign for our SAE latents being interpretable and monosemantic!). However, they found that autointerp on randomized SAE latents performed better than one might expect, because even random latents will display patterns when you take the top-k over a very large dataset (e.g. always firing on the same token or something). Can you replicate these results? What do you think the results say about autointerp and SAEs as a whole?

- Incorporating more information. Can you add to the generation prompt in ways suggested by EleutherAI, such as (1) adding the top logits boosted by this latent, (2) giving the quantized activation values for each token, (3) including example explanations in your prompt which illustrate the different kinds of latents you might encounter (e.g. token-level, substring-level, or concept-level with high consistent activation heuristic), or (4) using chain of thought to improve the quality of the model's explanations, for example:

Step 1: List a couple activating and contextual tokens you find interesting. Search for patterns in these tokens, if there are any. Don't list more than 5 tokens.

Step 2: Write down general shared latents of the text examples.

Step 3: List the tokens that the neuron boosts in the next token prediction.

Step 4: Write an explanation.

Patch scoping

Now, we'll move on to patch scoping, an interesting new method for autointerp which promises to significantly cut down the compute costs of running autointerp on a very large set of SAE latents. To summarize, patch scoping involves taking a prompt like "The meaning of X is" and then generating output from the same model which the SAE was trained on, steering on the token X in the direction of the SAE latent. Effectively we're taking advantage of the model's own internal representations to get it to define a latent for us, as opposed to just using a different model to automate assessments of latents based on their activations.

We'll be using the instruction-tuned Gemma 2B model for this exercise, so before we start the exercise we'll need to briefly address instruction tuned models and how they work. If you're comfortable with the basics of IT models, you can feel free to skip this section.

Instruction-tuned models

Instruction tuning is a technique for fine-tuning LLMs on a labeled dataset of instructional prompts and corresponding outputs. It improves model performance not only on specific tasks, but on following instructions in general. Note that instruction tuning is not the same thing as RLHF - it doesn't require any RL in the optimization process, it's just fine-tuning in the same way as you might have performed the fine-tuning exercises in the first chapter of ARENA material (when we studied image classifiers).

The training data in instruction tuning ususally consists of 3 elements:

- An instruction: A natural language text input that specifies a given task. For example, “translate this sentence from English to Spanish.”

- Additional information: Optional, supplementary information that provides context relevant to the task at hand. For example, an input for a reading comprehension task might include a brief passage (and then instruct the model to answer a given question about it).

- Desired output: The target output—response—for the given prompt, per the instructions and context provided. This will serve as a ground truth against which the model’s predictions are evaluated and optimized.

For example, here's an example from the UltraChat dataset (with some of the content removed for brevity):

[

{

"content": "Here is a piece of text: SEOUL, SOUTH KOREA — In the final game of their historic match, Google's artificially intelligent Go-playing computer system has defeated Korean grandmaster Lee Sedol, finishing the best-of-five series with four wins and one loss.\nThe win puts an exclamation point on a significant moment for artificial intelligence. Over the last twenty-five years, machines have beaten the best humans [...] There are holes in its education. But, able to draw on months of play with itself—on a corpus of moves that no human has even seen—it also has the ability to climb out of such a deep hole, even against one of the world's best players. AI is flawed. But it is here.\n\nBased on the text material above, generate the response to the following quesion or instruction: Assess the advantages and disadvantages of a machine like AlphaGo compared to a human player like Lee Sedol in a game of Go.",

"role": "user",

},

{

"content": "One advantage of AlphaGo over Lee Sedol is that it doesn't feel pressure or get tired, and it can play for hours on end without losing focus. Additionally, AlphaGo uses deep neural networks to learn tasks by analyzing massive amounts of digital data, which allows it to make moves that no human would make. On the other hand, Lee Sedol can adjust his strategy based on his opponent's previous moves, but AlphaGo can't do so until it is retrained by its creators. Additionally, Lee Sedol was able to draw on his intuition and adapt to what he saw from his opponent in previous games, something AlphaGo can't do yet. However, even with its flaws, AlphaGo has shown that AI is a force to be reckoned with in complex games like Go.",

"role": "assistant"

}

]

The training process will involves formatting the above content into a single prompt, and then training on the loss from the model's predictions on the assistant text (not the user text). The details of training vary, and sometimes involve freezing earlier layers or using techniques like LORA (low-rank adaptation) which stop the model from changing too much during training. After all, we don't want to massively change what the model knows, we just want to steer it towards a certain way of responding.

One of the finnicky parts of using these models is that you need to make sure the prompts are formatted in the correct way. Below is some example code which loads in the instruction-tuned Gemma 2B model, and then generates a response using the expected format. Note - if you've not used the Gemma models before, we recommend you jump back to the section on GemmaScope & latent steering from section 1 (or at least skim that code to understand what the gemma models are and how to load them - you may have to authenticate with HuggingFace first to download the model).

Reminder - you can use huggingface-cli delete-cache to clear your cache if you're hitting storage constraints (see the content on GemmaScope in section 1 for more on this).

USING_GEMMA = os.environ.get("HUGGINGFACE_KEY") is not None

if USING_GEMMA:

gemma_2b_it = HookedSAETransformer.from_pretrained("google/gemma-2b-it", device=device)

prompt = "\n".join(

[

"<start_of_turn>user",

"Write a hello world program in python<end_of_turn>",

"<start_of_turn>model",

]

)

GENERATE_KWARGS = dict(temperature=0.5, freq_penalty=2.0)

output = gemma_2b_it.generate(prompt, max_new_tokens=150, **GENERATE_KWARGS)

print("\n" + output)

Let's also load in our SAEs. Note that we're using an SAE which was trained on gemma-2b (note this is not the same as the gemma-2-2b model we've worked with previously).

Why is it okay to use an SAE which was trained on the base model, not the instruction tuned model? The answer comes from some research as part of Neel Nanda's MATS stream, showing that

if USING_GEMMA:

# Display all SAEs trained on the base gemma-2b model

metadata_rows = [

[data.model, data.release, data.repo_id, len(data.saes_map)]

for data in get_pretrained_saes_directory().values()

if data.model == "gemma-2b"

]

print(

tabulate(

metadata_rows,

headers=["model", "release", "repo_id", "n_saes"],

tablefmt="simple_outline",

)

)

# Take a closer look at the SAE release we'll be using

sae_release = "gemma-2b-res-jb"

sae_id = "blocks.6.hook_resid_post"

release = get_pretrained_saes_directory()[sae_release]

print(

tabulate(

[

[k, repr(v)]

for k, v in release.__dict__.items()

if k not in ["saes_map", "neuronpedia_id"]

],

headers=["Field", "Value"],

tablefmt="simple_outline",

)

)

┌──────────┬─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┬──────────────────────────────────────┬──────────┐

│ model │ release │ repo_id │ n_saes │

├──────────┼─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┼──────────────────────────────────────┼──────────┤

│ gemma-2b │ gemma-2b-res-jb │ jbloom/Gemma-2b-Residual-Stream-SAEs │ 5 │

│ gemma-2b │ sae_bench_gemma-2-2b_sweep_standard_ctx128_ef2_0824 │ canrager/lm_sae │ 180 │

│ gemma-2b │ sae_bench_gemma-2-2b_sweep_standard_ctx128_ef8_0824 │ canrager/lm_sae │ 240 │

│ gemma-2b │ sae_bench_gemma-2-2b_sweep_topk_ctx128_ef2_0824 │ canrager/lm_sae │ 180 │

│ gemma-2b │ sae_bench_gemma-2-2b_sweep_topk_ctx128_ef8_0824 │ canrager/lm_sae │ 240 │

└──────────┴─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┴──────────────────────────────────────┴──────────┘

┌────────────────────────┬──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Field │ Value │

├────────────────────────┼──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ release │ 'gemma-2b-res-jb' │

│ repo_id │ 'jbloom/Gemma-2b-Residual-Stream-SAEs' │

│ model │ 'gemma-2b' │

│ conversion_func │ None │

│ expected_var_explained │ {'blocks.0.hook_resid_post': 0.999, 'blocks.6.hook_resid_post': 0.71, 'blocks.10.hook_resid_post': -0.2, 'blocks.12.hook_resid_post': -0.65, 'blocks.17.hook_resid_post': -0.85} │

│ expected_l0 │ {'blocks.0.hook_resid_post': 47.0, 'blocks.6.hook_resid_post': 56.0, 'blocks.10.hook_resid_post': 62.0, 'blocks.12.hook_resid_post': 62.0, 'blocks.17.hook_resid_post': 54.0} │

│ config_overrides │ None │

└────────────────────────┴──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

We can see that SAEs trained on layers 0 and 6 seem to perform well, although this doesn't seem to be the case for the later layer SAEs. Let's load in the SAE trained on layer 6, and take a look at it.

Why can we use an SAE trained on the base model, but run forward passes on our instruction tuned model? That is to say, why should we assume that base model features will also be features of the SAE? One answer can be found in the post SAEs (usually) Transfer Between Base and Chat Models, which shows that the performance in various metrics (e.g. cross entropy loss recovered or percentage of variance explained) is still strong when you take an SAE trained on the base model and evaluate it on the IT model.

if USING_GEMMA:

gemma_2b_sae = SAE.from_pretrained(sae_release, sae_id, device=str(device))[0]

print(

tabulate(

gemma_2b_sae.cfg.__dict__.items(), headers=["name", "value"], tablefmt="simple_outline"

)

)

┌──────────────────────────────┬──────────────────────────┐

│ name │ value │

├──────────────────────────────┼──────────────────────────┤

│ architecture │ standard │

│ d_in │ 2048 │

│ d_sae │ 16384 │

│ activation_fn_str │ relu │

│ apply_b_dec_to_input │ False │

│ finetuning_scaling_factor │ False │

│ context_size │ 1024 │

│ model_name │ gemma-2b │

│ hook_name │ blocks.6.hook_resid_post │

│ hook_layer │ 6 │

│ hook_head_index │ │

│ prepend_bos │ True │

│ dataset_path │ HuggingFaceFW/fineweb │

│ dataset_trust_remote_code │ True │

│ normalize_activations │ none │

│ dtype │ torch.float32 │

│ device │ cuda │

│ sae_lens_training_version │ 2.1.1 │

│ activation_fn_kwargs │ {} │

│ neuronpedia_id │ gemma-2b/6-res-jb │

│ model_from_pretrained_kwargs │ {} │

└──────────────────────────────┴──────────────────────────┘

Exercise - implement patch scoping

Now, let's implement patch scoping. The method is:

- Take a prompt asking the model to define a particular term (you're given the prompt below). Note that we use the unknonwn token

"<unk>"instead of"X"as a stand-in for our latent, in line with the suggested improvement here. - Generate output with the model, steering on the token

Xin the direction of the SAE latent. We'll just do this by replacing the residual stream vectorresid_preat layerreplacement_layerwith the SAE latent vector, scaled so that its L2 norm equalsscale. This needs to happen at every position in the sequence whereXappears.

We'll be using this latent as an example:

if USING_GEMMA:

latent_idx = 607

display_dashboard(sae_release, sae_id, latent_idx)

A few tips while you're generating output:

- You can use the same

GENERATE_KWARGS-based output code we used in the above cell (you might also want to setverbose=False). - The way caching works for this model, the first token you generate will have shape

(batch_size=1, seq_len, d_model)but for every subsequent token the shape will be(1, 1, d_model)because we'll only be computing the residual stream values for the newly generated token (we only need the key and value vectors for previous token positions in order to fully determine the output - see the bonus section in the first day of ARENA transformers material for more on key-value caching). So you'll want to add this logic in thehook_fn_patch_scopingfunction; only replacing activations with the latent vector when the sequence length dimension of the activations is greater than 1.

def hook_fn_patch_scoping(

activations: Float[Tensor, "batch pos d_model"],

hook: HookPoint,

seq_pos: list[int],

latent_vector: Float[Tensor, "d_model"],

) -> None:

"""

Steers the model by returning a modified activations tensor, with some multiple of the steering

vector added to it.

Note that because of caching, this will be (1, seq_pos, d_model) the first time, and for every

subsequent token it will be (1, 1, d_model) - see previous exercises in this chapter to revisit

how KV caching works and why this is the case. You should only replace the activation with the

latent vector once, i.e. in the first forward pass.

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

def generate_patch_scoping_explanation(

model: HookedSAETransformer,

sae: SAE,

prompt: str,

latent_idx: int,

replacement_layer: int,

scale: float,

max_new_tokens: int = 50,

):

"""

Generates text with steering.

The steering vector is taken from the SAE's decoder weights for this particular latent. The

steering magnitude is computed from the `steering_strength` parameter, as well as the maximum

activation of this latent `max_act` (which has been computed from `find_max_activation`).

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

if USING_GEMMA:

GENERATE_KWARGS["verbose"] = False

scale_list = list(range(0, 60, 10))

replacement_layer = 2

prompt = "\n".join(

[

"<start_of_turn>user",

f'What is the meaning of the word "{gemma_2b_it.tokenizer.unk_token}"?<end_of_turn>',

"<start_of_turn>model",

f'The meaning of the word "{gemma_2b_it.tokenizer.unk_token}" is "',

]

)

for scale in scale_list:

output = generate_patch_scoping_explanation(

gemma_2b_it,

gemma_2b_sae,

prompt,

latent_idx,

replacement_layer,

scale,

max_new_tokens=50,

)

output_split = output.removeprefix(prompt).split('"')[0].strip().rstrip(".")

print(f"scale {scale:02} | {output_split!r}")

Click to see the expected output

scale 00 | 'of what importance or significance' scale 10 | 'for example' scale 20 | 'a small, hard seed that grows inside a fruit or legume' scale 30 | 'a seed, kernel, or fruit that has a hard outer shell and contains a kernel' scale 40 | 'a seed, kernel, or fruit enclosed in a shell' scale 50 | 'a seed that has been dried and roasted, and is often used for food'

Solution

def hook_fn_patch_scoping(

activations: Float[Tensor, "batch pos d_model"],

hook: HookPoint,

seq_pos: list[int],

latent_vector: Float[Tensor, "d_model"],

) -> None:

"""

Steers the model by returning a modified activations tensor, with some multiple of the steering

vector added to it.