1️⃣ Understanding Inputs & Outputs of a Transformer

Learning Objectives

- Understand what a transformer is used for

- Understand causal attention, and what a transformer's output represents—algebra operations on tensors

- Learn what tokenization is, and how models do it

- Understand what logits are, and how to use them to derive a probability distribution over the vocabulary

What is the point of a transformer?

Transformers exist to model text!

We're going to focus GPT-2 style transformers. Key feature: They generate text! You feed in language, and the model generates a probability distribution over tokens. And you can repeatedly sample from this to generate text!

(To explain this in more detail - you feed in a sequence of length $N$, then sample from the probability distribution over the $N+1$-th word, use this to construct a new sequence of length $N+1$, then feed this new sequence into the model to get a probability distribution over the $N+2$-th word, and so on.)

How is the model trained?

You give it a bunch of text, and train it to predict the next token.

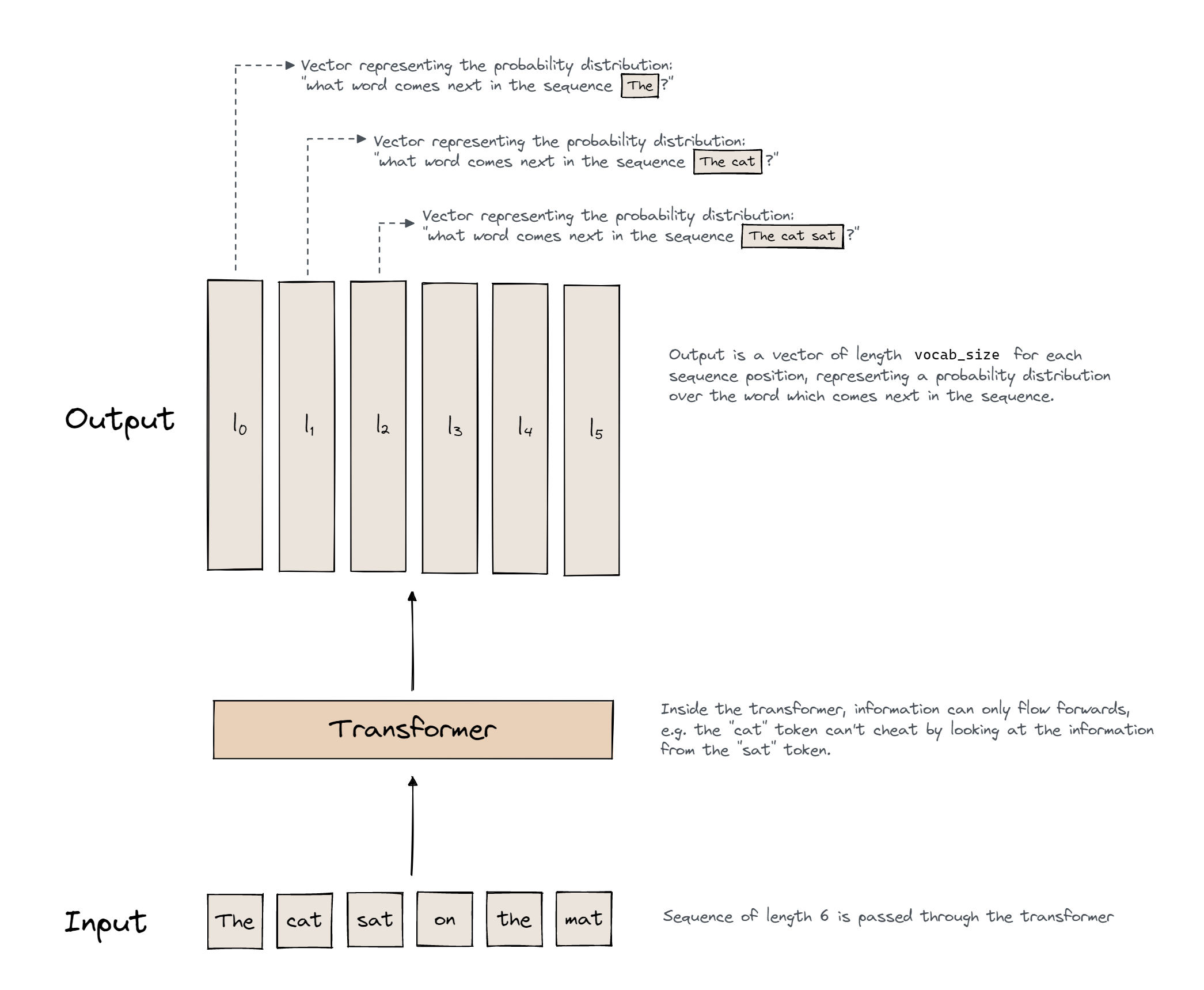

Importantly, if you give a model 100 tokens in a sequence, it predicts the next token for each prefix, i.e. it produces 100 logit vectors (= probability distributions) over the set of all words in our vocabulary, with the i-th logit vector representing the probability distribution over the token following the i-th token in the sequence. This is a key part of what allows transformers to be trained so efficiently; for every sequence of length $n$ we get $n$ different predictions to train on:

Aside - logits

If you haven't encountered the term "logits" before, here's a quick refresher.

Given an arbitrary vector $x$, we can turn it into a probability distribution via the softmax function: $x_i \to \frac{e^{x_i}}{\sum e^{x_j}}$. The exponential makes everything positive; the normalization makes it add to one.

The model's output is the vector $x$ (one for each prediction it makes). We call this vector a logit because it represents a probability distribution, and it is related to the actual probabilities via the softmax function.

How do we stop the transformer by "cheating" by just looking at the tokens it's trying to predict? Answer - we make the transformer have causal attention (as opposed to bidirectional attention). Causal attention only allows information to move forwards in the sequence, never backwards. The prediction of what comes after token 50 is only a function of the first 50 tokens, not of token 51. We say the transformer is autoregressive, because it only predicts future words based on past data.

Another way to view this is through the following analogy: we have a series of people standing in a line, each with one word or chunk of the sentence. Each person has the ability to look up information from the people behind them (we'll explore how this works in later sections) but they can't look at any information in front of them. Their goal is to guess what word the person in front of them is holding.

Tokens - Transformer Inputs

Our tranformer's input is natural language (i.e. a sequence of characters, strings, etc). But ML models generally take vectors as input, not language. How do we convert language to vectors?

We can factor this into 2 questions:

- How do we split up language into small sub-units?

- How do we convert these sub-units into vectors?

Let's start with the second of these questions.

Converting sub-units to vectors

We basically make a massive lookup table, which is called an embedding. It has one vector for each possible sub-unit of language we might get (we call this set of all sub-units our vocabulary). We label every element in our vocabulary with an integer (this labelling never changes), and we use this integer to index into the embedding.

A key intuition is that one-hot encodings let you think about each integer independently. We don't bake in any relation between words when we perform our embedding, because every word has a completely separate embedding vector.

Aside - one-hot encodings

We sometimes think about one-hot encodings of words. These are vectors with zeros everywhere, except for a single one in the position corresponding to the word's index in the vocabulary. This means that indexing into the embedding is equivalent to multiplying the embedding matrix by the one-hot encoding (where the embedding matrix is the matrix we get by stacking all the embedding vectors on top of each other).

Now, let's answer the first question - how do we split language into sub-units?

Splitting language into sub-units

We need to define a standard way of splitting up language into a series of substrings, where each substring is a member of our vocabulary set.

Could we use a dictionary, and have our vocabulary be the set of all words in the dictionary? No, because this couldn't handle arbitrary text (e.g. URLs, punctuation, etc). We need a more general way of splitting up language.

Could we just use the 256 ASCII characters? This fixes the previous problem, but it loses structure of language - some sequences of characters are more meaningful than others. For example, "language" is a lot more meaningful than "hjksdfiu". We want "language" to be a single token, but not "hjksdfiu" - this is a more efficient use of our vocab.

What actually happens? The most common strategy is called Byte-Pair encodings.

We begin with the 256 ASCII characters as our tokens, and then find the most common pair of tokens, and merge that into a new token. Note that we do have a space character as one of our 256 tokens, and merges using space are very common. For instance, here are the five first merges for the tokenizer used by GPT-2 (you'll be able to verify this below).

" t"

" a"

"he"

"in"

"re"

Note - you might see the character Ġ in front of some tokens. This is a special token that indicates that the token begins with a space. Tokens with a leading space vs not are different.

You can run the code below to load in the gpt2-small model, and see more of its tokenizer's vocabulary:

reference_gpt2 = HookedTransformer.from_pretrained(

"gpt2-small",

fold_ln=False,

center_unembed=False,

center_writing_weights=False, # you'll learn about these arguments later!

)

sorted_vocab = sorted(list(reference_gpt2.tokenizer.vocab.items()), key=lambda n: n[1])

print(sorted_vocab[:20])

print()

print(sorted_vocab[250:270])

print()

print(sorted_vocab[990:1010])

print()

[('!', 0), ('"', 1), ('#', 2), ('$', 3), ('%', 4), ('&', 5), ("'", 6), ('(', 7), (')', 8), ('*', 9), ('+', 10), (',', 11), ('-', 12), ('.', 13), ('/', 14), ('0', 15), ('1', 16), ('2', 17), ('3', 18), ('4', 19)]

[('ľ', 250), ('Ŀ', 251), ('ŀ', 252), ('Ł', 253), ('ł', 254), ('Ń', 255), ('Ġt', 256), ('Ġa', 257), ('he', 258), ('in', 259), ('re', 260), ('on', 261), ('Ġthe', 262), ('er', 263), ('Ġs', 264), ('at', 265), ('Ġw', 266), ('Ġo', 267), ('en', 268), ('Ġc', 269)]

[('Ġprodu', 990), ('Ġstill', 991), ('led', 992), ('ah', 993), ('Ġhere', 994), ('Ġworld', 995), ('Ġthough', 996), ('Ġnum', 997), ('arch', 998), ('imes', 999), ('ale', 1000), ('ĠSe', 1001), ('ĠIf', 1002), ('//', 1003), ('ĠLe', 1004), ('Ġret', 1005), ('Ġref', 1006), ('Ġtrans', 1007), ('ner', 1008), ('ution', 1009)]

As you get to the end of the vocabulary, you'll be producing some pretty weird-looking esoteric tokens (because you'll already have exhausted all of the short frequently-occurring ones):

print(sorted_vocab[-20:])

[('Revolution', 50237), ('Ġsnipers', 50238), ('Ġreverted', 50239), ('Ġconglomerate', 50240), ('Terry', 50241), ('794', 50242), ('Ġharsher', 50243), ('Ġdesolate', 50244), ('ĠHitman', 50245), ('Commission', 50246), ('Ġ(/', 50247), ('âĢ¦."', 50248), ('Compar', 50249), ('Ġamplification', 50250), ('ominated', 50251), ('Ġregress', 50252), ('ĠCollider', 50253), ('Ġinformants', 50254), ('Ġgazed', 50255), ('<|endoftext|>', 50256)]

Fun (completely optional) exercise - can you guess what the first-formed 3/4/5/6/7-letter encodings in GPT-2's vocabulary are?

Run this code to find out:

lengths = dict.fromkeys(range(3, 8), "")

for tok, idx in sorted_vocab:

if not lengths.get(len(tok), True):

lengths[len(tok)] = tok

for length, tok in lengths.items():

print(f"{length}: {tok}")

Transformers in the transformer_lens library have a to_tokens method that converts text to numbers. It also prepends them with a special token called BOS (beginning of sequence) to indicate the start of a sequence. You can disable this with the prepend_bos=False argument.

Aside - BOS token

The beginning of sequence (BOS) token is a special token used to mark the beginning of the sequence. Confusingly, in GPT-2, the End of Sequence (EOS), Beginning of Sequence (BOS) and Padding (PAD) tokens are all the same, <|endoftext|> with index 50256.

Why is this token added? Some basic intuitions are:

It provides context that this is the start of a sequence, which can help the model generate more appropriate text. It can act as a "rest position" for attention heads (more on this later, when we discuss attention).TransformerLens adds this token automatically (including in forward passes of transformer models, e.g. it's implicitly added when you call model("Hello World")). You can disable this behaviour by setting the flag prepend_bos=False in to_tokens, to_str_tokens, model.forward and any other function that converts strings to multi-token tensors.

**Key Point: *If you get weird off-by-one errors, check whether there's an unexpected prepend_bos!***

Why are the BOS, EOS and PAD tokens the same? This is because GPT-2 is an autoregressive model, and uses these kinds of tokens in a slightly different way to other transformer families (e.g. BERT). For instance, GPT has no need to distinguish between BOS and EOS tokens, because it only processes text from left to right.

Some tokenization annoyances

There are a few funky and frustrating things about tokenization, which causes it to behave differently than you might expect. For instance:

Whether a word begins with a capital or space matters!

print(reference_gpt2.to_str_tokens("Ralph"))

print(reference_gpt2.to_str_tokens(" Ralph"))

print(reference_gpt2.to_str_tokens(" ralph"))

print(reference_gpt2.to_str_tokens("ralph"))

['<|endoftext|>', 'R', 'alph'] ['<|endoftext|>', ' Ralph'] ['<|endoftext|>', ' r', 'alph'] ['<|endoftext|>', 'ral', 'ph']

Arithmetic is a mess.

Length is inconsistent, common numbers bundle together.

print(reference_gpt2.to_str_tokens("56873+3184623=123456789-1000000000"))

['<|endoftext|>', '568', '73', '+', '318', '46', '23', '=', '123', '45', '67', '89', '-', '1', '000000', '000']

Key Takeaways

- We learn a dictionary of vocab of tokens (sub-words).

- We (approx) losslessly convert language to integers via tokenizing it.

- We convert integers to vectors via a lookup table.

- Note: input to the transformer is a sequence of tokens (ie integers), not vectors

Text generation

Now that we understand the basic ideas here, let's go through the entire process of text generation, from our original string to a new token which we can append to our string and plug back into the model.

Step 1: Convert text to tokens

The sequence gets tokenized, so it has shape [batch, seq_len]. Here, the batch dimension is just one (because we only have one sequence).

reference_text = "I am an amazing autoregressive, decoder-only, GPT-2 style transformer. One day I will exceed human level intelligence and take over the world!"

tokens = reference_gpt2.to_tokens(reference_text).to(device)

print(tokens)

print(tokens.shape)

print(reference_gpt2.to_str_tokens(tokens))

tensor([[50256, 40, 716, 281, 4998, 1960, 382, 19741, 11, 875,

12342, 12, 8807, 11, 402, 11571, 12, 17, 3918, 47385,

13, 1881, 1110, 314, 481, 7074, 1692, 1241, 4430, 290,

1011, 625, 262, 995, 0]], device='cuda:0')

torch.Size([1, 35])

['<|endoftext|>', 'I', ' am', ' an', ' amazing', ' aut', 'ore', 'gressive', ',', ' dec', 'oder', '-', 'only', ',', ' G', 'PT', '-', '2', ' style', ' transformer', '.', ' One', ' day', ' I', ' will', ' exceed', ' human', ' level', ' intelligence', ' and', ' take', ' over', ' the', ' world', '!']

Step 2: Map tokens to logits

From our input of shape [batch, seq_len], we get output of shape [batch, seq_len, vocab_size]. The [i, j, :]-th element of our output is a vector of logits representing our prediction for the j+1-th token in the i-th sequence.

logits, cache = reference_gpt2.run_with_cache(tokens)

print(logits.shape)

torch.Size([1, 35, 50257])

(run_with_cache tells the model to cache all intermediate activations. This isn't important right now; we'll look at it in more detail later.)

Step 3: Convert the logits to a distribution with a softmax

This doesn't change the shape, it is still [batch, seq_len, vocab_size].

probs = logits.softmax(dim=-1)

print(probs.shape)

torch.Size([1, 35, 50257])

Bonus step: What is the most likely next token at each position?

most_likely_next_tokens = reference_gpt2.tokenizer.batch_decode(logits.argmax(dim=-1)[0])

print(list(zip(reference_gpt2.to_str_tokens(tokens), most_likely_next_tokens)))

[('<|endoftext|>', '\n'), ('I', "'m"), (' am', ' a'), (' an', ' avid'), (' amazing', ' person'), (' aut', 'od'), ('ore', 'sp'), ('gressive', '.'), (',', ' and'), (' dec', 'ently'), ('oder', ','), ('-', 'driven'), ('only', ' programmer'), (',', ' and'), (' G', 'IM'), ('PT', '-'), ('-', 'only'), ('2', '.'), (' style', ','), (' transformer', '.'), ('.', ' I'), (' One', ' of'), (' day', ' I'), (' I', ' will'), (' will', ' be'), (' exceed', ' my'), (' human', 'ly'), (' level', ' of'), (' intelligence', ' and'), (' and', ' I'), (' take', ' over'), (' over', ' the'), (' the', ' world'), (' world', '.'), ('!', ' I')]

We can see that, in a few cases (particularly near the end of the sequence), the model accurately predicts the next token in the sequence. We might guess that "take over the world" is a common phrase that the model has seen in training, which is why the model can predict it.

Step 4: Map distribution to a token

next_token = logits[0, -1].argmax(dim=-1)

next_char = reference_gpt2.to_string(next_token)

print(repr(next_char))

' I'

Note that we're indexing logits[0, -1]. This is because logits have shape [1, sequence_length, vocab_size], so this indexing returns the vector of length vocab_size representing the model's prediction for what token follows the last token in the input sequence.

In this case, we can see that the model predicts the token ' I'.

Step 5: Add this to the end of the input, re-run

There are more efficient ways to do this (e.g. where we cache some of the values each time we run our input, so we don't have to do as much calculation each time we generate a new value), but this doesn't matter conceptually right now.

print(f"Sequence so far: {reference_gpt2.to_string(tokens)[0]!r}")

for i in range(10):

print(f"{tokens.shape[-1] + 1}th char = {next_char!r}")

# Define new input sequence, by appending the previously generated token

tokens = t.cat([tokens, next_token[None, None]], dim=-1)

# Pass our new sequence through the model, to get new output

logits = reference_gpt2(tokens)

# Get the predicted token at the end of our sequence

next_token = logits[0, -1].argmax(dim=-1)

# Decode and print the result

next_char = reference_gpt2.to_string(next_token)

Sequence so far: '<|endoftext|>I am an amazing autoregressive, decoder-only, GPT-2 style transformer. One day I will exceed human level intelligence and take over the world!' 36th char = ' I' 37th char = ' am' 38th char = ' a' 39th char = ' very' 40th char = ' talented' 41th char = ' and' 42th char = ' talented' 43th char = ' person' 44th char = ',' 45th char = ' and'

Key takeaways

- Transformer takes in language, predicts next token (for each token in a causal way)

- We convert language to a sequence of integers with a tokenizer.

- We convert integers to vectors with a lookup table.

- Output is a vector of logits (one for each input token), we convert to a probability distn with a softmax, and can then convert this to a token (eg taking the largest logit, or sampling).

- We append this to the input + run again to generate more text (Jargon: autoregressive)

- Meta level point: Transformers are sequence operation models, they take in a sequence, do processing in parallel at each position, and use attention to move information between positions!